1593

John Penry wept for Wales. In Elizabeth’s England, there were far too few pastors assigned to teach the Welsh, and of those, many were absentees from their flocks or little better than rogues. Penry wrote Equity of a Humble Supplication in Behalf of the Country of Wales that Some Order May Be Taken for the Preaching of the Gospel Among Those People. He complained that thousands in Wales had almost never heard of Christ. “O destitute and forlorn condition! Preaching itself in many parts is unknown. In some places a sermon is read once in three months.” He proposed a system of lay pastors supported in part with voluntary gifts from the people. His attack on the neglectful practices of the Church of England won Penry the undying enmity of John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Having become a Puritan separatist in his thinking, Penry could not accept a state-run system, because, as he phrased it, “The truth of Christ and ministry of Christ as it is his will be in bondage unto no antichristian power. If it be, it is antichrist’s truth and ministry.” Because of such outspoken views, and his stern warnings to the queen and her bishops, Penry had to flee at times. Eventually he would be hanged, making him a hero and martyr in Wales.

What sealed his doom was The Marprelate Tracts. These were satirical exposés larded with heavy-handed taunts at English bishops (“petty popes”), coarse talk (“Printed overseas, in Europe, within two furlongs of a bouncing priest”) and silly sneers (“Ha, ha, Dr. Copycat!”). Their theme can be summed up in the words of the first tract: “Leave you your wickedness and I’ll leave the revealing of your knaveries.” An example of the knavery was confiscation of stolen cloth by one bishop for his own use. “Well, one or two of the thieves were executed and at their deaths confessed that to be the cloth which the bishop had, but the dyers could not get their cloth, nor cannot unto this day…” Penry was thought to have a hand in preparing the popular pamphlets although he denied it. While it is true that they were printed on the same press as his books, the general consensus today is that he did not write them. They weren’t his style.

Captured, he was treated to a travesty of justice. Some strong words of warning against Elizabeth in his notebook were interpreted as treason. Archbishop Whitgift was the first to sign his death warrant. Penry was hauled off to be hanged on this day, May 29, 1593. A thin scattering of bystanders, none of them his friends, watched as the 34-year old departed this world at the end of a rope about four in the afternoon. He was not allowed to preach a final sermon.

He had, however, written a lengthy letter to his four daughters (Deliverance, Comfort, Safety and Sure Hope), none of whom was old enough to really understand yet what was going on; the eldest was four years, the youngest four months. In it he showed his deep affection for them: “Wherefore, again, my daughters, even my tenderly beloved daughters, regard not the world or anything that is therein…” He implored them to follow true faith: “And I, your father, now ready to give my life for the former testimony do charge you, as you shall answer in the day of the Lord, to embrace this my counsel given unto you in His name, and to bring up your posterity after you (if the Lord vouchsafe you any) in this same true faith and way to the Kingdom of Heaven.”

1810

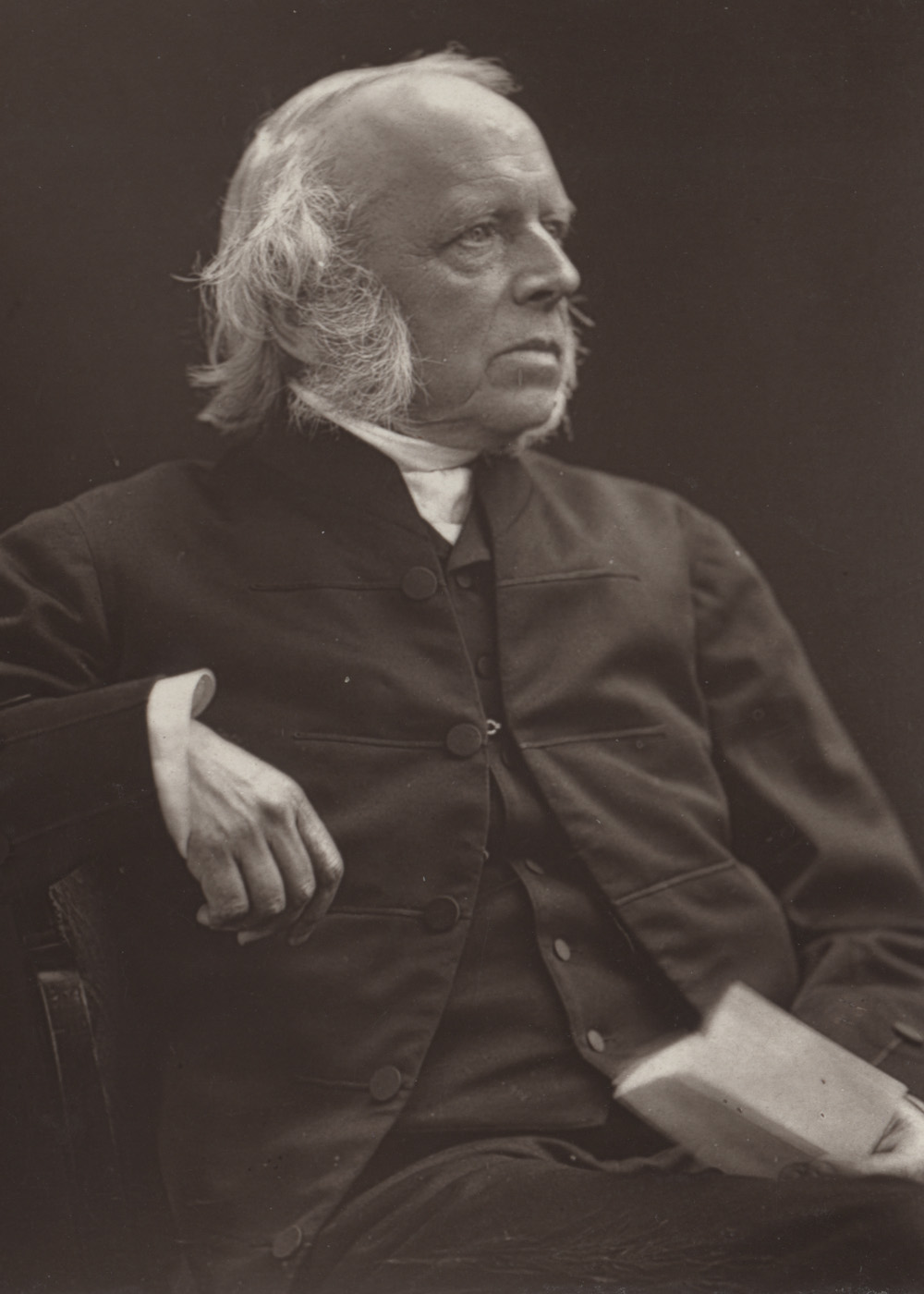

I have learned by experience that it is not much labor but much prayer that is the only means to success,” said Andrew Bonar. A leader of the revival in Scotland known as the Kilsyth Revival, Andrew knew about success; his secret was that he lived in prayer. “I have been endeavoring to keep up prayer…every hour of the day, stopping my occupation, whatever it is, to pray a little. I seek to keep my soul within the shadow of the throne of grace and Him that sits thereon.”

To a friend he wrote, “…rather neglect friends than not pray, rather fast, and lose breakfast, dinner, supper and sleep too — than not pray.”

Andrew was born in Edinburgh on this day, May 29, 1810. His father died when he was just seven. One of his older brothers helped his mother feed the many mouths left without a father. As a boy Andrew did well in school, becoming one of the best Latin students of his day. He was modest about his accomplishments, however. For example, when he won a gold medal, he said nothing about it until his mother asked which student had won it. With a high sense of what it meant to become a minister, he waited two years until he was sure that he was “in Christ” before he began divinity studies. He had tried to become pure enough to enter Christ’s kingdom until at last he realized that he never could but that Christ had met God’s expectations on his behalf.

After studying theology at the great university in his hometown, Andrew became a minister, first at Collace and then in Glasgow. Like his older brother, Horatius (the hymn writer) he joined the Free Church when it formed in 1843.

Among Andrew’s close friends were some of the most notable preachers of the day, including the pure and zealous Robert Murray McCheyne, with whom he traveled to Palestine to see how the Jews fared there. When McCheyne died shortly afterward, Andrew said, “There was no friend whom I loved like him.” He penned McCheyne’s biography.

Other losses followed: an infant son and his wife. Two years later he recorded in his diary how he nearly broke down in the pulpit remembering his beloved Isabella.

Examples of Andrew’s preaching show that it was simple and practical. For example, reminding his listeners that Christ sang a hymn just before he left for Gethsemane, where he would be betrayed, Andrew said, “His last note was a cheerful note, though He knew what was in the future. Much more should ours be so. Let us try unselfishly, like Jesus, to keep our friends from sorrow as long as we can. In the face of difficulties, sing to the Lord. If you have a dread of what is coming, sing, instead of brooding over it.”

Andrew wrote several books on Bible topics. From time to time readers sent him letters telling how they were converted through his works. Among his interesting titles was Christ and His Church in the Book of Psalms. He wrote of it, “May the Lord use it to lead many to see their full provision in Christ!” When Andrew died in 1892, he was the last of his siblings to go. He had gathered his children around his bed and read the Bible and prayed with them.