1724

If Beethoven is the poster child for unexpected results from a faulty ancestry, Henry Venn could stand for predictable results from a good line. His great-great grandfather William Venn became a Protestant clergyman during the Reformation. William’s son Richard was dispossessed of his church position by Parliament because he favored the king during the English civil war. Richard’s son Dennis and grandson Richard (father of Henry Venn) were both pastors in the Church of England.

Henry Venn was born at Barnes in Surrey on this day 2 March 1724. Even as a boy, he was passionate about Christianity, refusing the friendly overtures of a minister who was reputed to deny the divinity of Christ, saying, “I will not come near you! for you are an Arian.”

Not surprisingly, he followed in family tradition and entered the ministry. Whereas the ministry was merely a living for not a few clergymen who frittered their time in gaming and fox hunting, Venn’s strong sense of duty caused him to even give up cricket, which he loved. He became one of the pioneering evangelical preachers of England around the same time that Whitefield and Wesley began to preach. However, fellow clergymen attacked him vehemently.

When he was thirty-five, Venn left an appointment at Clapham, where he was experiencing little success, to accept a position at Huddersfield—a position with much greater duties for the same pay. His wife balked at the move initially but changed her mind when she saw a throng of souls saved in the new parish. The Huddersfield church, almost empty before Venn began work, soon could not hold the crowds who came to hear his exhortations. He exerted himself so strenuously that his health failed completely. In part this was because, after the death of his wife, he had to rear his five children alone.

Spitting blood and expecting to die soon, Venn resigned from his pulpit twelve years after coming to Huddersfield and became a rector at the small country parish of Yelling. There his health rebounded. He was able to write books and many letters and to share the gospel in friendly pulpits on the side. He also counseled young men who were attending college at Cambridge.

Venn educated his children at home. Their lessons could be unusual. For example, after promising to show his children one of the most interesting sights in the world, he led them to a squalid hut where a young man was dying in poverty and misery. The young man’s face and voice were aglow with joy, however, at the near prospect of meeting Christ face to face.

The family tradition of ministry continued long after Henry Venn died. Remembering the unique lessons of his father, John Venn became a prominent evangelical in the Church of England. Henry Venn’s grandson, also named Henry, became a missionary-statesman in the Church of England, who argued for giving native converts leadership of their own churches. A great-grandson, Charles John Elliot, also became an evangelical clergyman. Charlotte Elliot, author of the hymn “Just As I Am,” was Venn’s granddaughter.

1938

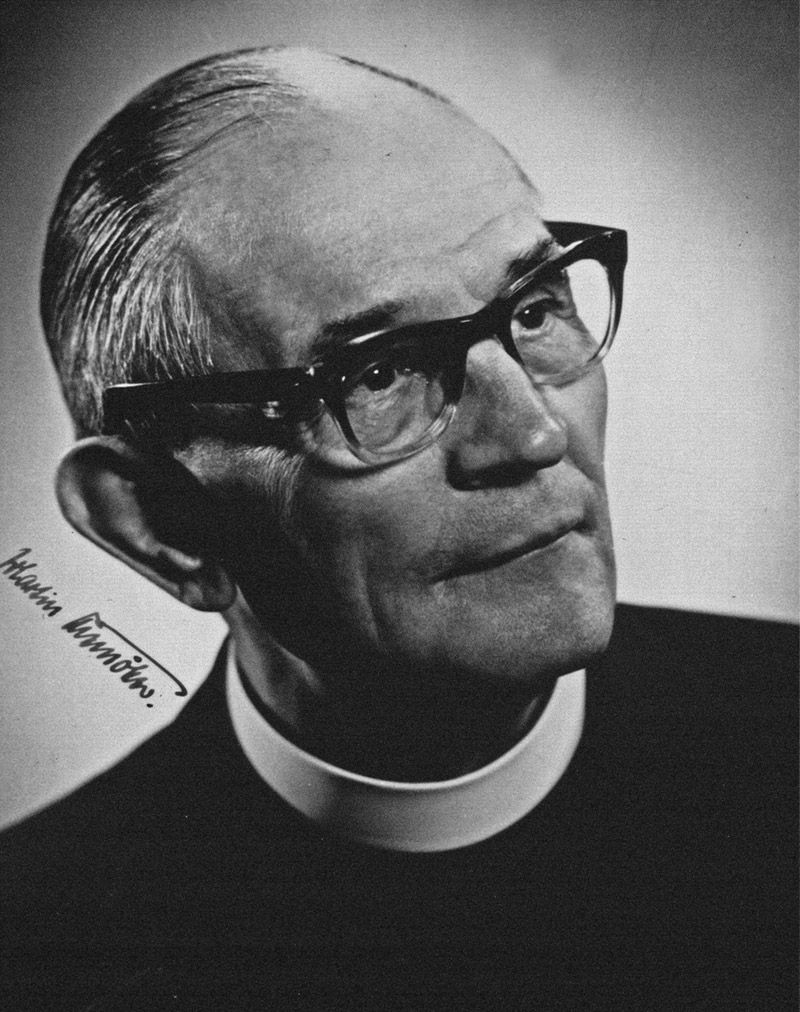

The results of some trials are foregone conclusions. In the case of Martin Niemöller the words of Hitler ensured that any court appearance would be perfunctory. Niemöller had delivered a “rebellious” sermon in 1937 and Hitler heard of it and of taped phone conversations in which Niemöller repudiated the Nazi line. Bent on obtaining absolute control over the church, Hitler flew into a rage and bellowed that Niemöller was to be placed in a concentration camp and kept there for life since he had proven himself “incorrigible.”

It is true that Niemöller had helped organize a “resistance” to Hitler’s takeover of the Protestant churches, a group called the Pastor’s Emergency League. “…we have called into being an ‘Emergency Alliance’ of pastors who have given one another their word in a written declaration that they will be bound in their preaching by the Holy Scripture and the Reformation confessions alone…” he wrote in an open letter September 1933. This group developed into the Confessing Church. Nonetheless, he apologized with deep regret in October 1945, after the war, for failing to speak out early and strongly enough against Nazism:

When the Nazis came for the communists,

I remained silent;

I was not a communist.

When they locked up the social democrats,

I remained silent;

I was not a social democrat.

When they came for the trade unionists,

I did not speak out;

I was not a trade unionist.

When they came for the Jews,

I did not speak out;

I was not a Jew.

When they came for me,

there was no one left to speak out.

However, there were plenty of “German Christians” who did not resist at all; who thought that Christ had come through Hitler and their first task was to be German, not Christian. Pastor Leutheuser verbalized their thoughts. Niemöller, an ex-submarine captain, was appalled at this attitude. Christ was to be central in every Christian’s heart. 7,000 Lutheran ministers agreed with him. Niemöller, until his imprisonment, was their strategist. Karl Barth joined this Confessing Church in writing a rejection of the state’s claim to totalitarian power in religious and political matters. This became known as the Barmen Declaration.

Although Niemöller was the symbol of Protestant resistance to Hitler, he has been accused of anti-semitism because he preached that the Jews will suffer until they embrace Christ.

In prison, he wrote many letters. On February 8, 1938 the second day of his trial, he wrote to his wife Else, “Give my greetings to the congregation and tell them that I place my entire confidence in God’s mercy, and that I am convinced that one day we will recognize in the light the paths along which he leads us now in the darkness and that we will praise his wisdom! God does not desire to give us earthly hopes, but he will certainly not abandon us. Jesus Christ remains the same, that is certain; and God will grant us that “we remain with him!” The trial ended on this day, March 2, 1938, and afterward he was sentenced to seven months in prison. Hitler had him arrested again almost as soon as he was released. This time his resistance placed him in concentration camps at Sachsenhausen and Dachau until the end of the war. Altogether he spent eight years in prison.

When Niemöller visited the hotel where Albert Speer, a Hilter associate, was held after the war, Speer expected to see a broken man. Instead, it was a healthy and youthful figure he saw who had emerged from the camps. Perhaps a clear conscience had helped keep him so.