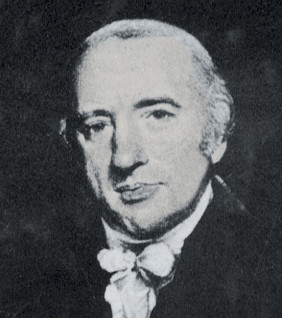

1779

SHORTLY AFTER COMING TO CAMBRIDGE on 29 January 1779, Charles Simeon faced a serious test of conscience. “It was but the third day after my arrival that I understood I should be expected in about three weeks to attend the Lord’s Supper…The thought rushed through my mind that Satan himself was as fit to attend as I; and that if I must attend, I must prepare for my attendance there.” Until then, he had been more concerned with clothes than with Christ, spending the large sum of £50 a year on his wardrobe.

Without delay he bought The Whole Duty of Man—the only religious book he had heard of. Fasting, praying, reading, confessing, and crying to God for mercy, he got through his first Holy Communion. He knew he would have to take the sacrament again at Easter and read a book on how to prepare for the Lord’s Supper. His sins oppressed his mind so much that he found himself wishing he might exchange his life for that of a dog so that he would not have to face eternity.

Simeon’s misery lasted for weeks. However, his reading brought him a new understanding—that Christ was his sacrificial substitute:

The thought came to my mind, What, may I transfer all my guilt to another? Has God provided an Offering for me, that I may lay my sins on His head? Then, God willing, I will not bear them on my own soul one moment longer. Accordingly I sought to lay my sins upon the sacred head of Jesus…

He began to have hope. Early this morning, 4 April 1779, Easter Sunday, he awoke with these words on his heart and lips: “Jesus Christ is Risen Today; Hallelujah! Hallelujah!” From that hour, peace flowed into his soul. At chapel, taking Communion, he felt close to God and saw that all his sins were buried in Christ’s grave.

Simeon eventually became the vicar of Trinity Church, Cambridge. He preached a direct, forthright gospel—one for which his congregation was not prepared. Some boycotted him, and the church wardens locked him out of his own church. Drunken students mocked him and threw stones through the chapel windows. The congregation even chose other pastors to give their Sunday afternoon lectures. Though opposition continued for thirty years, interested listeners rose to over a thousand during the same time.

Simeon persevered and became a leader of the Evangelical wing of the Church of England in the early 19th century. Many of the students who attended his chapel adopted his methods, and he even bought control of church vacancies so that he could appoint Evangelicals throughout England. He was active in forming the British and Foreign Bible Society, the Religious Tract Society, the Church Missionary Society, and a society to evangelize Jews. Several of his spiritual children became chaplains to India. Among them was Henry Martyn, who became famous as a Bible translator in India and Persia.

Simeon was so active and influential that his name crops up frequently in biographies and histories of the early nineteenth century. He never lost his zeal, preaching and evangelizing until just weeks before his death in 1836. He was known for his deep love for the Book of Common Prayer.