Here’s this week’s inspirational delve into the past by Paul James-Griffiths of Christian Heritage Edinburgh. Paul begins a new series focusing on Scotland’s mission to the nations, the bulk of which will be in the 19th century. We start today with the background to how the world mission started.

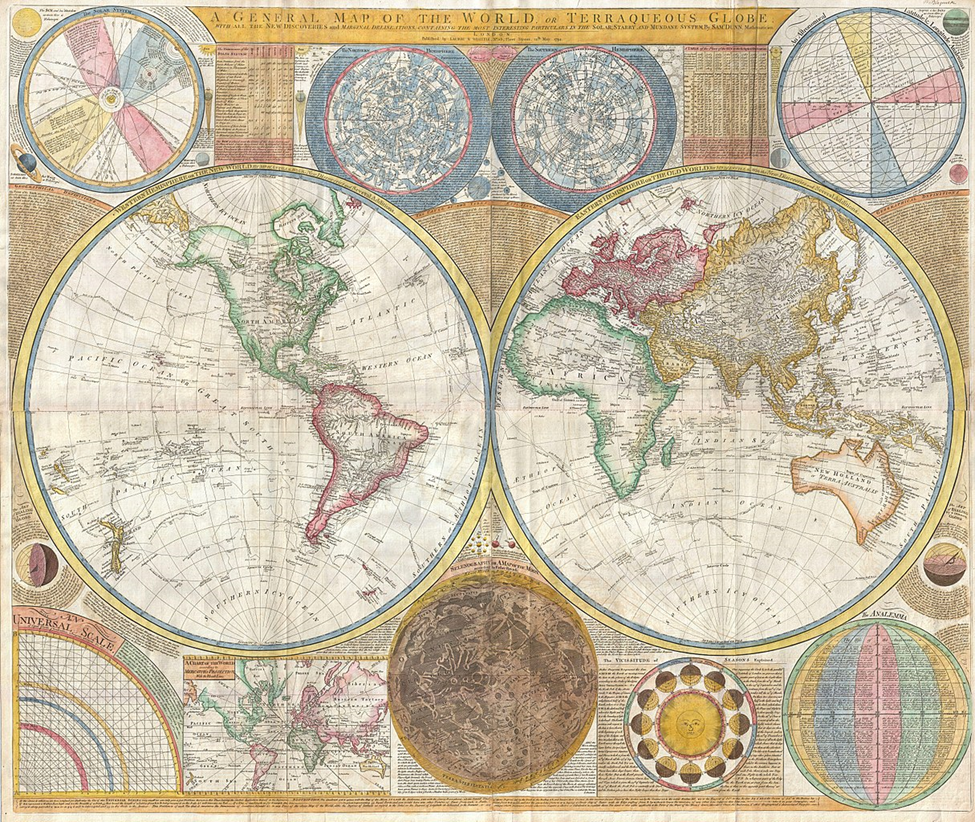

Image: Map of the World by Samuel Dunn in 1794, artist Thomas Kitchin,

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Shortly before his execution as a leader of the Covenanters in 1680, Revd Richard Cameron prophesied that “our Lord is to set up a standard, and oh that it may be carried to Scotland! When it is set up, it shall be carried through the nations…” It was the view of some of the key Covenanters like Cameron and Revd James Renwick, who was executed in Edinburgh in 1688, that a great revival movement would break out in Scotland, and that missionaries would be sent from here to the nations to see God’s kingdom set up. Such a call to world mission was already established in the vision of the Scottish Reformation church, but we had to go through centuries of persecution and refining to get the house of God in order, followed by the deadening influence of liberalism, before a mighty army of missionaries was raised up and sent forth, both at home and abroad.

In the Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology we read:

“The true origins of Scottish overseas mission lie in the confluence of two streams… One flows from the Scottish Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge [SSPCK]… The second stream comes from the evangelical awakening of 1742 [Revd George Whitefield’s Cambuslang revival].”

Already in 1709 SSPCK’s founding document in Edinburgh stated, in section six, that their vision was “To extend their endeavours for the advancement of the Christian Religion, to Heathen Nations; and for that end, to give encouragement to ministers to preach the Gospel among them.”

At first SSPCK financially supported three missionaries among the North America Indians in 1730, and later the well-known missionary, David Brainerd, was also supported by them between 1743 and 1747. In 1767 the New Testament in Gaelic was published as missionaries were sent to evangelise the Highlanders in Scotland, most of whom had a thin Roman Catholic veneer, covering a faith more akin to pagan folklore. As such, Scotland itself became a good training ground for missionaries. By 1774 support was raised for two black missionary Africans, Bristol Yamma and John Quamine, to be trained in theology by Revd Dr John Witherspoon, the Scots evangelical scholar and statesman who had immigrated to America. Sadly, the American War of Independence put a stop to this mission to West Africa. With Revd Dr John Erskine’s call for world mission to the Church of Scotland Assembly in 1796, the movement for change was growing.

The watershed moment for world mission came in 1824, when the Church of Scotland moved from seeing mission as “a very low and drivelling concern” to become a vibrant vision, full of faith and potential. The Moderates’ emphasis on education and social action was being combined with the Evangelicals’ commitment to preaching the gospel. From this moment onwards the church’s call to world mission became sharper and sharper, like someone adjusting a telescope until the clarity was rich and focused. Scotland, despite its small population, became a leader in sending out missionaries, and Edinburgh became an epicentre for training them up.

Over the next weeks I shall seek to bring to light the extraordinary missionary movement that erupted from Scotland, especially during the 19th century, and which brought about the transformation of many nations.

“Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations” (Matthew 28:19, NKJV).