Here’s this week’s inspirational delve into the past by Paul James-Griffiths of Christian Heritage Edinburgh. Paul writes, “This week’s focus is about an extraordinary missionary called Alexander Duff, whose model for higher education had a huge impact on shaping India, and whose work inspired many other missionaries to go and do likewise in many parts of the world.”

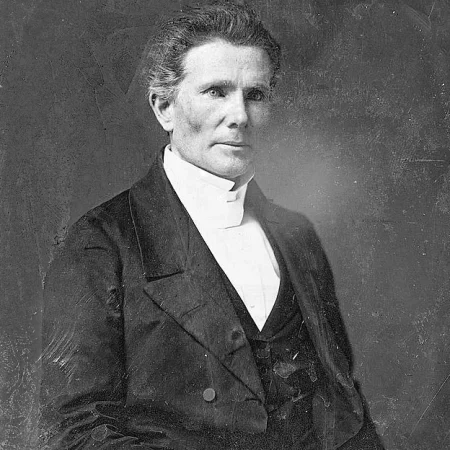

Image: Revd Dr Alexander Duff (1806-1878).

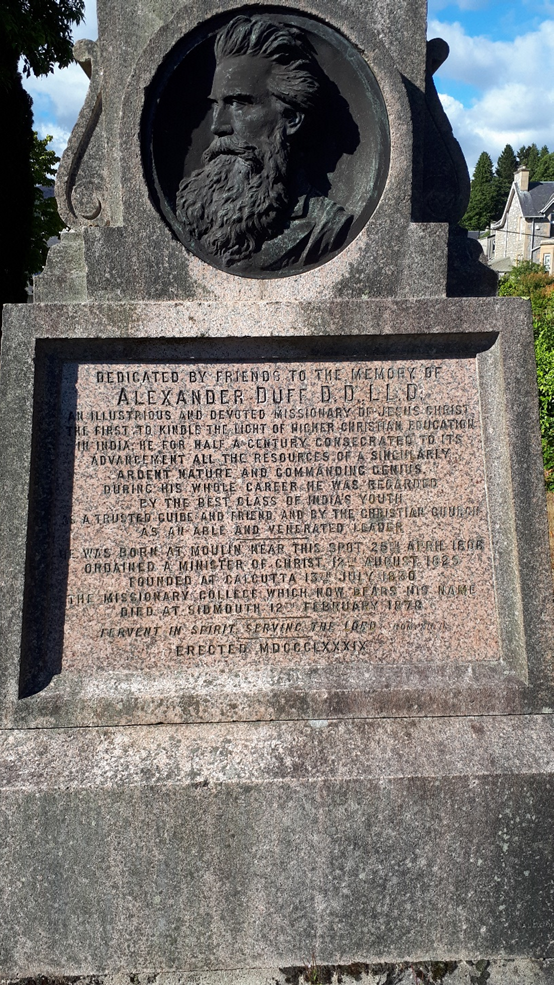

His memorial at Moulin Parish Church, Perthshire. Photo by Paul James-Griffiths

Between 1827 and 1834 Dr Chalmers’ remaining five students all left for India. Of these, Alexander Duff was the best known. His vision was to reach the Brahmin high caste culture in Calcutta by opening up a Christian school in 1830 for Hindus to learn and practice the English language – an entirely different method to other missionaries, like the Englishman William Carey at Serampore, who learnt the native languages to reach the people of the lower, oppressed castes, and established the first vernacular college there in 1818, with Joshua Marshman as its principal.

Duff followed Chalmers’ “grand design”, teaching all subjects from a Christian perspective, endeavouring to train up future Indian leaders with a Christian worldview, which he believed in time would spread throughout India to transform the nation. Duff was convinced that all truth was God’s truth, and so his “downward filtration” theory was established, hoping that by this India would undergo a slow, but increasingly Christian reformation from the top down. He began at age twenty-four, and by the end of his time abroad he had become known as “the prince of missionaries to India.”

After the initial opposition from the Hindu parents and pupils, Duff and his fellow missionaries, William Sinclair MacKay and David Ewart, from the St Andrews Seven, saw a breakthrough. MacKay, who acted as the Superintendent for the Church of Scotland Mission School in Calcutta, found a huge hunger for the New Testament classes. “Their eagerness to get it was such”, he said, “that we could not enter the room where they were taught, without being persecuted to give it to them.”

By 1837 the General Assembly’s Institution in Calcutta, which was later called Duff’s College, had 700 pupils, which was the largest mission school in India. Every so often there would be a spate of new baptisms as eager students pressed in to follow Christ, meaning that the numbers of college attendees would fluctuate as Hindu and Muslim parents pulled their children out, but would rise up again because of the good reputation of the education there. For example, in 1845, the enrolments fell from 1,300 to 618, but by 1862 there were 1,723 pupils, including 211 girls. Duff’s policy of the kingdom yeast in the dough of Indian culture was paying off.

In 1871 there were forty-eight Hindu and Muslim converts, and of them nine became church ministers, ten became Bible teachers, seventeen became professors and higher-grade teachers, eight were government officials, and four were assistant surgeons and doctors. Hindu Brahmins who became Christians could now shake off the racist caste system, and operate as surgeons on the black-skinned “untouchables”; they could influence India’s national policy in government and education. They could also sit down as equals with lower castes and enjoy communion together.

The University of Calcutta itself grew out of Duff’s ministry when it was established in 1857, as part of the initiative for establishing India’s first three universities, a vision driven by the Scottish Christians Duff and Lord Macaulay, with Englishman, Charles Trevelyan. Since its foundation, the University of Calcutta has gone on to produce heads of government, social reformers, leading scientists, and five Nobel laureates. In the first year as a university, the Calcutta Medical College was affiliated to it, becoming Asia’s first one, and Bethune College, India’s first college for women, as well as the first science college in India, were connected with Calcutta University, as it was called then.

When other missionaries came and set up colleges, they modelled what they did on Duff’s work, which meant that hundreds of their converts began to also influence Indian society at the top level. It is extraordinary that missionaries of the calibre of Duff, who came from a poor working-class background in Auchnahyle, in the parish of Moulin in Perthshire, could have such an impact in shaping nations. But then this was largely due to the Christian democratic structure of the Scottish Presbyterian Church.

“Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations” (Matthew 28:19, NKJV).