Of his latest article about Scottish missionaries, Paul James-Griffiths of Christian Heritage Edinburgh writes, “This week is all about the 19th century mission to the Jewish people in Budapest, Hungary, which was one key influence of the modern Messianic movement. “Rabbi” John Duncan pioneered this work, which proved to be very fruitful.”

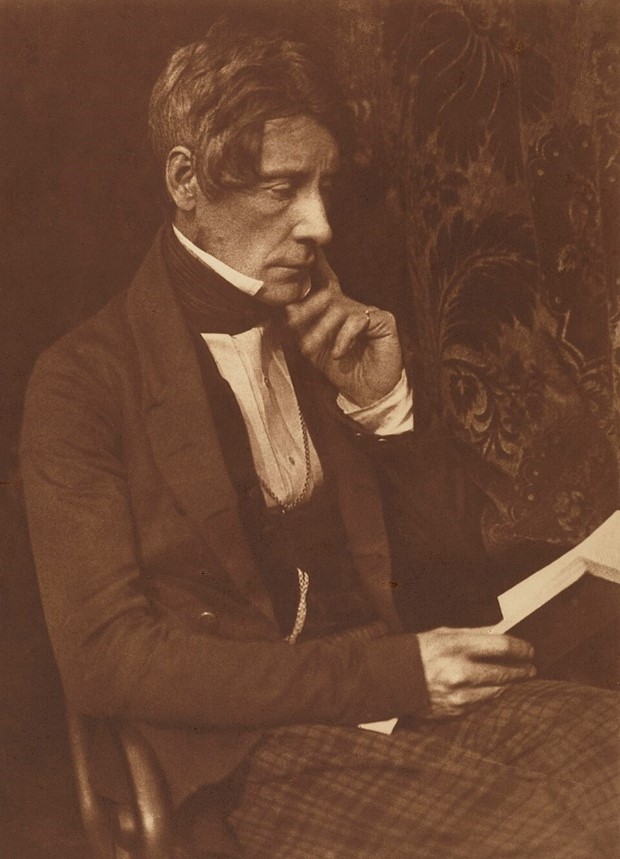

“Rabbi” Dr John Duncan (1796-1870)

by David Octavius Hill, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

One day a lady came on our Famous Lives Tour in 2019. Usually, we run this for a minimum of four people, but because she was so keen I did the tour just for her. When I met her, she was reading Professor Herman’s book, The Scottish Enlightenment: The Scots’ Invention of the Modern World. As we continued, she became more and more engrossed with what she was hearing, and when we arrived at the Presbytery Hall with the National Covenant and Disruption painting, she became ecstatic. As I began to point out the various influential missionaries on the painting, she pointed at a young boy holding a huge map of Palestine. “Who is that? Why has he got a map of Palestine?” she asked, with amazement. And so, I began to tell the story of the relationship between the Scottish Presbyterians and the Jewish people.

“You may have noticed,” I said, “that the church where we began is called St Columba’s Free Church, but its architecture is so different to the elaborate churches of other denominations. It has a simplicity about it; it looks more like a…”

“Synagogue!” she exclaimed.

“Exactly!” I answered. “You see, in the Scottish Reformation of the 16th century we peeled away all of the coverings that had grown over the church during the centuries, and sought to bring it back to a more biblical model. This is expressed by the simple buildings, but we also stood by the National Covenant, which was signed by over 300,000 Scots, or about a third of the population. Only Israel had made such national covenants before that time.”

“Oh, I thought of God’s covenants as you showed me the National Covenant earlier,” she said, full of excitement.

“The Presbyterians had a special love for Jewish people,” I continued. “So, you see this map of Palestine? The boy wasn’t actually there at the 1843 Disruption event, when the evangelical movement left the Church of Scotland to establish the Free Church of Scotland, but he is next to “Rabbi” Dr John Duncan [1796-1870].”

“Rabbi? In a church?” she queried, with a puzzled look on her face.

“Well, no,” I laughed. “He wasn’t Jewish, but he became a very learned professor of Hebrew in Edinburgh, and he was a pioneer of mission amongst the Jewish people. The boy next to him in the painting grew up to be Dr Adolph Saphir [1831-1891], who was among the first Jewish believers in Jesus in Budapest. He came to Edinburgh with “Rabbi” Duncan and Alfred Edersheim, another Jewish man who accepted Jesus as Messiah in Hungary. This scholar, Dr Edersheim [1825-1889], wrote an influential book called The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. In this book he demonstrated from the Jewish Tanakh [Old Testament] and Talmud that Jesus is the promised Messiah for the Jews.”

“No way!” interjected the Jewish lady. “I’ve grown up all my life in the synagogue, and nobody has ever told me such things. We were told that Jesus is only for the Goyim [Gentiles], not for the Jewish people.”

“Edersheim demonstrated that there are at least 456 places in the Tanakh which are predictions pointing to Jesus as Messiah,” I said.

“If this is true, then why don’t more Jewish people accept Jesus?” she replied.

“Well,” I explained, “throughout the ages hundreds of thousands of Jewish people have believed. As a result of the mission in Budapest pioneered by Duncan in 1841, hundreds of Jewish people also accepted Jesus. Some of them went to their Jewish people in Eastern Europe, seeing others there believe in the Messiah too; then some went to America, where others became believers. There was a movement of God in 19th century America in which hundreds of Jewish people became followers of Messiah, including some rabbis. Sadly, church history is riddled with centuries of persecution against the Jewish people by the church, but Scottish Presbyterians used to love the Jewish people, and Scotland is one of the few European countries that never persecuted its own Jewish population.”

“What about Israel?” she asked. “What’s your opinion about a Jewish state?”

“Love for the Jewish people also meant a love for the Jewish Scriptures,” I said. “The Tanakh clearly says that the Jewish people will return to Israel. This was believed by centuries of Christians, too. The Scottish Christians also played a significant part in this.”

“How come?” the lady asked, deeply focused and intrigued.

“Look at this group of men,” I said, pointing at the right side of the Disruption Painting. “Here’s Professor Black and Dr Keith. They went out to Palestine with Revd Robert Murray McCheyne and Revd Andrew Bonar in 1839 to explore the situation there on behalf of the Church of Scotland. For centuries Presbyterians believed from the Bible that God would bring the Jewish people back to Israel in preparation for them receiving the Messiah. The Covenanter Presbyterians who suffered so much for their faith preached about this and publicly prayed for it during the “Killing Time” [1661-1688]. Have you heard of the Balfour Declaration?” I asked.

“Yes, of course,” she replied, “every Jewish person knows about this.”

“Did you know that former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour was a Scottish Presbyterian, and that of the nine-man cabinet for discussing the view that the Jewish people should be allowed to settle again in Palestine, three were Scottish Presbyterians and a fourth was an Ulster-Scots Presbyterian?” I asked.

“No, I didn’t know that,” she replied.

“It was the Presbyterian passion from Scotland that influenced many evangelical Christians in Europe and America, who in turn influenced those in power so that when the Balfour Declaration was passed in 1918, there was Gentile support for Jewish repatriation in Israel. This is something that the Jewish Zionists, Theodore Herzl, Chaim Weizmann, and Louis Brandeis, all recognized. The final return of the Jewish people came about when the United Nations, which had been primed by the Balfour Declaration, voted in favour of the rebirth of Israel.”

Two hours later this Jewish woman from a Canadian synagogue left, clutching a Gospel of John and a booklet of the testimonies of five Jewish people who had accepted Jesus as Messiah, including two rabbis. Her eyes and facial expression said it all, but her parting words were: “Thank you for this tour. I have grown up in synagogues all my life where we were told never to talk to born again Christians. For the last three hours I have had the most enlightening time of my life. I will always remember this.”