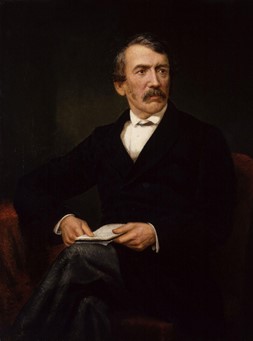

Paul James-Griffiths of Christian Heritage Edinburgh writes, “This week’s article is about Dr David Livingstone, the famous Scottish missionary. Although very few Africans were converted to Christ through him, his success lay in preparing the way for others to come and plant churches. Even until today he is spoken of with great affection by many Africans.”

David Livingstone (1813-1873) was a household name in Britain in the Victorian era, but for six years he had disappeared in Africa. This enigmatic, stubborn, missionary adventurer lay desperately ill in the town of Ujiji next to Lake Tanganyika in Tanzania. Another explorer called Sir Henry Morton Stanley was sent to find him and arrived in 1871 to find the sickly Scotsman. He greeted him with the well-known words, “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”

Livingstone has become one of the most famous missionaries, but his legacy was not in establishing thriving churches of African converts, but in leaving behind a manly model of courage and raw determination, against huge obstacles, which inspired generations of missionaries to forsake all and give them themselves to the cause of world mission. It was Livingstone’s exploration work and mapping of central Africa that opened up the way for many others to pursue his vision for Christianity, commerce, and civilization. During the 1960s when statues of white colonialists in Africa were removed and names of cities and towns were changed to African names, two towns named after David Livingstone remained: Livingstone in Zambia, and Livingstonia in Malawi, showing the great respect the locals had for this man.

David Livingstone, like many of the Scots missionaries, came from a poor background, but went on to have an enormous influence. He grew up in the Presbyterian Church in Blantyre, near Glasgow, where he worked in a cotton factory doing monotonous jobs from the age of ten for twelve hours a day. His dedicated Christian father encouraged his children to learn, so David became an avid reader. Apart from his father’s enthusiasm for spreading the gospel, other Christians had a considerable influence on David as he developed into a man: one of these was the Revd Ralph Wardlaw, whose vocal stance against slavery stirred many, and another was the missionary Karl Gützlaff, whose book, Appeal to the Churches of Britain and America on behalf of China, inspired David to combine his love of science and the gospel as a medical missionary. After being enthused by Gützlaff’s appeal for medical missionaries in China in 1834, Livingstone worked hard and saved up the money necessary for an education at Anderson University in Glasgow, as well as studying theology at Glasgow University.

He had originally hoped to be a medical missionary in China with the London Missionary Society (LMS), but the Opium Wars prevented this. In the same period, he prepared for the mission field with LMS in London as a medical student at the Charing Cross Hospital Medical School, where he met Robert Moffat whose pioneering work in South Africa inspired Livingstone to seek a post to Africa. At the same time Livingstone was struck with admiration for the evangelical Christian, T.F. Buxton. William Wilberforce had passed his baton on to this politician and social reformer in the long battle against slavery, and Buxton was promoting the idea of a combination of Christianity and commerce to defeat the slave trade in Africa. Livingstone believed that his calling to be a medical missionary in Africa would also include a strong stand against slavery there.

On 20th November 1840, Livingstone was ordained as a missionary with LMS and he left Britain for South Africa shortly afterwards, arriving in Cape Town in March, 1841. For the next thirty-two years he poured himself out for God’s cause in Africa, often drawing close to death through disease. He only saw one known person converted to Christ; a pagan chief called Sechele, at Kolobeng. Livingstone hesitated to baptize him because he had five wives and was not sure this man was serious about following Christ. Sechele divorced four of the wives, but later had a child through one of them; he also practiced some pagan beliefs, so Livingstone moved on, disappointed at the outcome. However, it was through Chief Sechele that multitudes of people from the Kwena tribe of Botswana turned to Christianity – albeit with a pagan mixture.

Supporters at home became frustrated with Livingstone, who increasingly saw that his role in Africa was to prepare the way for other missionaries, whereas they were looking for results in terms of new Christians. He felt frustrated that the mission board could not see that by exploring Africa and mapping out the main rivers and towns, he was opening up the way for others to establish churches, schools, and healthcare, and to abolish the slave trade. He broke with LMS and found funding for his enterprise through the British government who saw the value of what he was doing, because he was also easing the way for trade for the African Lakes Company.

Often intrepid visionaries can be difficult to work with, and so it was with Livingstone. Not only did he fall out with various teams sent to work with him, but he was also so consumed with his mammoth work that he neglected his wife and children, becoming a fleeting figure in their lives. His ministry was really the work of a rugged single man, facing dangers on every hand. His place too, in the history of abolition of slavery, is important in Africa. His determination to end slavery endeared him to many, but also made enemies of the Swahili-Arab Muslims who made a lucrative career out of the lives of innocent people, although at times they also cared for him when he was so ill.

Zanzibar in Tanzania was one of the important slave markets in East Africa, and mainly through Livingstone’s work the British government brought slavery to an end. Today, Christ Church, the Anglican Cathedral, stands on the site of the huge slave market that was once there, with its altar being placed on the spot where the whipping post had been. Inside the church tourists flock to see a simple cross made from the wood of the tree near to which David Livingstone’s heart was buried when he died in Chitambo, Zambia, in 1873. A party of natives held him in such high esteem that they travelled over 1,000 miles in sixty-three days to the coastal town of Bagamoyo, where a British ship took the coffin for the body to be buried in Westminster Abbey.