Of his latest article about Scottish missionaries, Paul James-Griffiths of Christian Heritage Edinburgh writes, “Usually I write shorter articles of about 600-700 words, but I just could not do justice to Mary Slessor, the missionary who went to Nigeria, with so few words. This time, I’m guilty of writing over 2,000 words! I hope you don’t mind. Mary is such an inspiration and I find her story deeply moving. I hope it will inspire you all too.”

At dawn the crowds excitedly pressed in to see the majestic canoe heading towards their village. With a crew of thirty-three natives paddling in unison, and a shelter on the boat designating royalty, it was an impressive sight. They were awaiting the long-expected trip of the White Queen of Calabar. When she stepped ashore, the small white lady with fiery red hair and joyous blue eyes was greeted by a multitude of admirers who held her in deep reverence. Quickly she was ushered into Chief Okon’s house with much exuberance. Mary Slessor of Dundee had arrived.

Of all the Scottish missionaries, Mary Slessor has caught the imagination more than most, with her image even being put on the Clydesdale £10 note. She came from an impoverished home due to her father’s addiction to alcohol, and grew up with abuse and violence, but she had a godly mother who prayed for her children and taught them the Bible. Stories of the exploits of missionaries in faraway lands were read to them, captivating the children, but the account which entranced Mary was that of Calabar in Nigeria. As a small girl she would play with her dolls, imagining that they were dark-skinned people from Calabar, and she would make stick people, lining them up and pretending they were African children being taught by her in a school.

From the age of eleven she accompanied her older brother Robert to the weaving mill, working a twelve-hour daily shift during the week. With their income, their father drank more alcohol, fuelling yet more guilt and violence. For Mary, her mother, and her siblings, Sunday was the highlight of the week during which they would walk to Wishart Church, named after the reformer, George Wishart, who was martyred for his faith at St Andrews. However, Mary had been Christianised but not converted. At the age of fifteen this all changed. One cold winter’s day, a neighbouring widow invited some of the girls into her home and spoke to them about God’s salvation. “Do you see that fire?” said the old widow, “If you put your hand into the flames, it would be very bad. It would burn you. But if ye dinna repent ‘n’ believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, your soul will burn in the lowin’, blazin’ fire forever and ever.”

This dramatic illustration so moved Mary that she sought out Christ and turned her life over to him. Straightaway she became a missionary to the children in the slums of Dundee where Wishart Church was based. In her zeal for Christ, with love in her heart, she would try and round up the children and take them to a mission hall. Sometimes she was met with violent threats. On one occasion a boy stood with a whip in his hand next to the mission. “Suppose we change places, what would happen?”she asked him. “I would get the whip across my shoulders,” he answered. “I will bear it for you, if you’ll go in,” she replied. The boy, never having met such love before, was melted and followed her meekly into the mission hall. It was these early days in her Christian life that revealed the godly calibre, confidence, and adventurous nature that oozed out of her. But she kept dreaming about Calabar.

She applied to the Foreign Mission Board with the United Presbyterian Church in 1876, requesting a teaching post in Calabar, after which she was accepted, providing she finished her studies in Dundee and at an Edinburgh Normal school (teacher training college).She was warned about the dangers of working in “the white man’s grave” in Calabar, but her reply was “my Master needs me there.”This was the hallmark of her life.

At the age of twenty-eight she arrived in Calabar, Nigeria, to take up her role as a teacher to the children in Duke Town. Whilst learning the Efik language she assisted the small missionary team there; this work had been established thirty years before and some progress had been made among the locals with churches and schools. Her longing though was to bring the message of Christ to those who had never heard of his love, in remote places where no missionary had ever trodden.

As she visited the villages outside Duke Town she found clusters of mud huts around the chief’s home. It was here that she began to see first-hand how the locals lived. In these villages the chiefs ruled with an autocratic and iron fist, with much cruelty and little mercy. They owned many wives and slaves, which they treated ruthlessly. Egbo, a secret society, was dreaded by many. Gangs from Egbo would suddenly appear with frightening masks, and with whips drive off innocent people into slavery, committing atrocities wherever they went.

When Mary expressed her passion to reach the outlying villages further afield, Mrs Anderson, one of the missionaries, tried to dissuade her: “Many are cannibals,” she said, “When a chief dies, his wives and slaves have their heads cut off and are buried with him. A slave receives no more consideration than a pig. They sleep on the ground like animals, and are branded with a hot iron. Many have their ears cut off, and the girls are fattened like animals and sold for slave wives. And one of the worst customs is the treatment of twins. The people fear twins worse than death. They are not allowed to live. They are killed, crushed into pots and thrown into the bush. The mother is driven out. No one will have anything to do with her, leaving her to die in the forests or be eaten by the animals.”

Instead of being scared off, Mary’s love for these people kept growing. In particular her motherly heart was broken by the plight of the twins in Nigeria. With tears in her eyes, she looked up at Mrs Anderson. With her resolute Scottish accent, she declared, “I shall fight this. It must be stopped… I will never give up.”

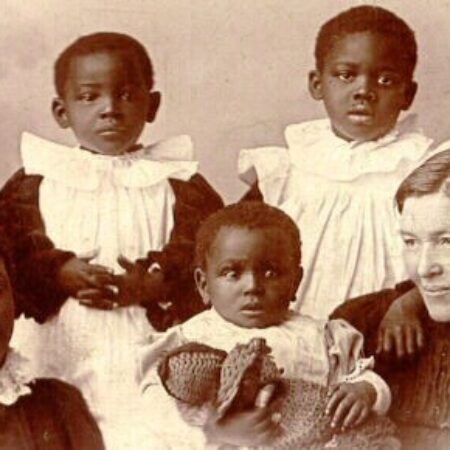

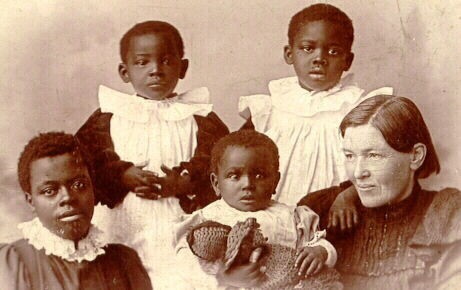

As opportunities arose, she pressed on further into the bush, witnessing scenes of huts full of human skulls from victims of cannibalism, and she discovered the reason for twin-killing. According to the belief of the tribes having twins was a sign that the mother had had an affair with an evil spirit. As nobody could discern which child belonged to the father, both children would have their backs broken and would be taken into the forest to rot or be devoured by wild beasts. Whenever Mary could rescue twin babies before this happened, she would do so, adopting them, and caring for them as a doting, nursing mother. At first the locals thought she was an evil witch for doing this, but in time she was respected as “the White Ma who loves babies.”

There came a time as she persevered, sharing the gospel of Christ, and caring for the people in every way she could, that the breakthrough she longed for came. One evening when she was sitting on the veranda with the children, a crowd of men appeared, loudly proclaiming that twins and twin-mothers could now live, and that if anyone harmed them, they would be hanged. With much clapping and tears pouring down their faces the women gathered to celebrate. “It was a glorious day for Calabar,” Mary wrote, “I wept tears of joy.”A few days later, when the legal papers were signed, such a great noise of celebration erupted from the women that Mary asked the chief to stop it. “Ma, how can I stop them women mouths?” he replied, “How can I do it? They be women.”

Despite this victory Mary knew that the only thing that would bring lasting change would be a genuine conversion to Christ and his ways. She knew from personal experience in Dundee that conversion of the heart, not Christianisation of the culture, was the key, but only God could do this miracle. As she persisted with her message, more and more locals began to experience this inward change, but she still ached to press on yet further into the darkness of the bush, so when Chief Okon asked for her to come to his people at a great distance upriver, she was excited. King Eyo Honesty VII in the Old Town lent her his royal canoe and paddlers, regarding this trip of great importance.

Dense Darkness

When she was shown into Chief Okon’s house she was put in his harem room, but she insisted on putting up a privacy screen. The house was infested with rats, insects and lizards, and the sweat of the chief’s wives beyond the screen was intoxicating. Crowds gathered everywhere to hear her preach about Jesus, and when she walked the jungle paths with the people, she would frequently come across human skulls, amulets, and images to the pagan gods. Often those with her would become almost paralysed with fear of the spirits and evil.

Once she intervened when two of Chief Okon’s teenage wives were to be given a hundred lashings each with the whip. Through her pleading she managed to reduce the punishment to ten each, and she bathed their wounds afterwards, caring for them. In her discussions with the leaders, they expressed a real interest in following Christ, but were concerned that if they reduced their harsh control of the people, they would lose respect and the people would rebel. Slowly and surely her example and message began to melt their hearts, just like the boy with the whip who had threatened to lash her so long ago in Dundee.

One day the opening came for the Okoyong people. By this time, she had become revered as the White Queen, or White Ma, and a request for a visit came from their leaders. Knowing full well the danger that lay before her, she set off with her team for the village of Ekenge. In this area she found a darkness far worse than she had ever encountered. Drunken orgies were commonplace, and debauchery of every kind. She discovered torture with boiling oil was used, and poisoning with beans. In these places, nobody ever physically abused her, because they revered her, but at times she was overcome with heartbreak. “Had I not my Saviour close beside me,” she said, “I would have lost my reason.”Her heart particularly went out to the women who were so often crushed and dejected, and used as objects, which could be tossed away as useless rags whenever it suited the men. Often tears streamed down her face as she witnessed the children being treated like animals for the pleasure of the tribe, as they forced them to get drunk on white man’s whisky.

As she persevered Mary began to see dramatic changes among the Okoyong. “Of results affecting the condition and conduct of our people,” she wrote, “Raiding, plundering and stealing of slaves have almost entirely ceased… No tribe formerly was so feared because of their utter disregard for human life. But human life is now safe. No chief ever died without the sacrifice of many lives, but the custom has now ceased… In regard to infanticide and twin-murder, there has dawned on them the fact that life is worth saving, even at the risk of one’s own.”

When the request came to visit the Ibo tribe, ruled harshly by the Aros clan, she realised that she was now entering the bastion of Nigerian culture. “I feel drawn on and on by the magnetism of this land of dense darkness and mysterious, weird forests,” she wrote, and promptly prepared to travel into the very heart of darkness. Here the juju god was believed to live in a special tree and each village had its sacred tree and god, with witchdoctors having great power over the people. Not far from Arochuku there was a small island in a lake, which was the centre of juju worship. It was to here that people from neighbouring villages and further afield would venture to consult the pagan priests. Often, they were seized by the priests and their men and sold into slavery, or were devoured by cannibals. Mary, an extraordinary woman, who trod where most men feared to go, started to preach to the people of a totally new life in Christ. When she had to leave, the tribesmen pleaded with her, “Come back soon, White Ma. If you do not care for us, who will care for us?”

It was this intrepid fearlessness and love for Christ, and for the tribes of Nigeria, that drove Mary on. After almost forty years of tireless work, she could write: “My life is one long, daily, hourly record of answered prayer.” As she lay dying in 1915, her bright blue, piercing eyes were still aflame with love for the Nigerians, who had become her people. Her legacy was a network of churches and schools, and transformed lives; treasures redeemed out of the heart of darkness.