1543

British Parliament prohibits the reading of the New Testament in English by “women or artificer’s prentices, journeymen, servingmen of the degree of yeoman, or under, husbandmen or labourers…”

1604

Puritan John Rainolds suggests to King James I “that there might bee a newe translation of the Bible, as consonant as can be to the original Hebrew and Greek.”

James will grant approval the next day. Seven years later, the Authorized Version (King James Version) will be published.

1756

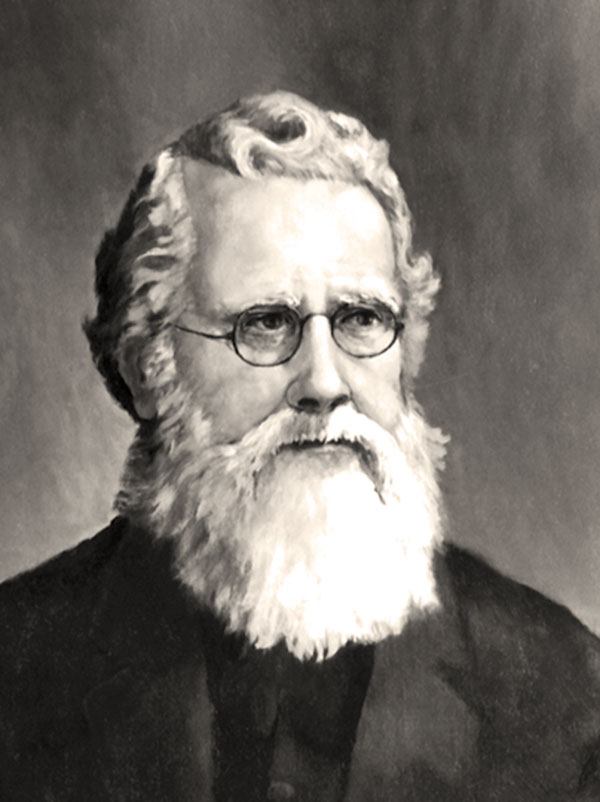

What if you asked your pastor how you could be rescued from God’s wrath and he said he didn’t know? That is what happened to Isaac Backus. The Great Awakening was in full swing in America. Evangelists wakened Americans to realize they needed to repent of sin, and Isaac was afraid.

When his pastor could not show him how to get right with God, Backus went about his business. For weeks he prayed desperately that God would show him how to save his soul. He felt powerless and very frightened. Peace came one morning as he mowed a field. “I was enabled by divine light to see the perfect righteousness of Christ and the freeness and riches of his grace,” he later wrote.

Backus was determined that no one else should suffer as he had by not knowing how to find salvation. He studied Scripture so that he could explain to others that Jesus took our sin to the cross with him and that forgiveness is ours if we confess our sins to God, believing he is able to restore us.

People noticed the young man’s zeal. Backus was about 22 when he began to preach and 24 when a little “separate” church in Middelborough, Massachusetts asked him to be their pastor. Separates were those who were converted in the Great Awakening and left the established church thinking its ministers were cold fish who knew theology but didn’t know Jesus Christ.

Aware of his great responsibility, young Backus pleaded earnestly with the Lord that “he wouldn’t suffer me to settle down in any snare or evil way.”

Backus would have stayed with the Separates, but when he changed his views on baptism, his congregation grew cold toward him. And so, on this day, January 16, 1756, he formed the first Baptist church in Middleborough. It is as a Baptist that Backus is famous. When he was born, there were only 1,500 Baptists in New England. When he died, there were 21,000– many of them converted through his efforts.

Backus is most famous for his long battle against taxation to supported state churches. It is wrong to force a person against their conscience, he said. “In Christ’s kingdom, each one has equal right to judge for himself.” His recorded the testimony of hundreds who suffered harassment because they refused to pay the religious tax. These included several members of Backus’s own family, who went to jail or lost their property. Once he himself was seized by a policeman, but someone paid the tax for him. Through letters, testimony and civil disobedience, Backus forced Massachusetts to face its religious problem. He made others aware of the situation, too, riding 1,200 miles a year on horseback to inform them about it. He printed pamphlets. But separation of church and state was not achieved until after he died.

Backus also had a hand in founding America’s first Baptist school of higher learning, Rhode Island College (Brown University).

1786

Some insurance policies award damages for lost fingers, eyes and other vulnerable body parts. What is a tongue worth in your contract? What are your ears valued at? For many centuries, people gave up their ears and tongues for their faith.

The problem was monopoly. A single denomination would control the faith of a country and everyone was taxed to support it. These established churches were often opposed to reforms, because they wanted to hang onto their privileges. Governments also preferred to have just one church because a single church is easier to oversee.

Authorities were severe with anyone who threatened church monopolies. A man might have his tongue cut off for preaching without a license. A citizen might lose his ears for listening to unapproved preaching. In the worst cases, rulers burned people to death for teaching children the Ten Commandments or the Lord’s Prayer.

But above all, church monopolists were afraid of commoners having access to the Bible. Religious authorities feared the laity would misinterpret Scripture, opening the door to spiritual and civic anarchy. For centuries, the Roman Church blocked ordinary people from laying eyes on Scripture. Even after the Protestant Reformation began, governments tried to keep the Bible away from commoners. For example, on this day, January 16, 1543, nine years after King Henry VIII became the head of the Church of England, Parliament passed a law making it illegal for any “women or artificer’s prentices, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen, or under, husbandmen or laborers to read the New Testament in English.” Commoners were hit!

Even after commoners won the right to read the Bible, established churches remained the norm. Germany and Sweden made Lutheranism their state churches. England had the Church of England. In Massachusetts, the Puritans ruled with severity toward Baptists and Quakers, whom they jailed, whipped exiled, or hanged. In Virginia, the Anglican Church was the established church until 1779. Anglican priests did not hesitate to demand the authorities jail Baptist preachers who competed with their monopoly.

Thomas Jefferson, then governor of Virginia, was disgusted. If you tell a man what to believe and punish him if he doesn’t, you may not change his mind but you might make a hypocrite of him. You are guilty for putting bait in his path, said Jefferson. For seven years, sometimes allied with Baptists and Presbyterians, Jefferson battled to pass an act establishing complete freedom of religion in his state. The Virginia Statute of Religious Liberty passed on this day, January 16, 1786, two hundred and forty three years to the day after Parliament passed its act making Bible reading illegal.

Jefferson’s act argued that “to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves, is sinful and tyrannical.” If you make an office available only if people will hold or renounce certain ideas, you encourage men to betray themselves for money. “Truth,” he said, “is great and will prevail if left to herself…” No one should suffer from the government on account of his religious beliefs. Everyone should be free to spread whatever religious opinions convince him. Jefferson did not argue that religion should be suppressed but only that the state must not make any form of it mandatory.

So proud was Jefferson of his role in obtaining this piece of legislation that he asked that his tombstone record it as one of his three great achievements. “Author of the Declaration of Independence, Founder of the University of Virginia, and Author of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom.”

1815

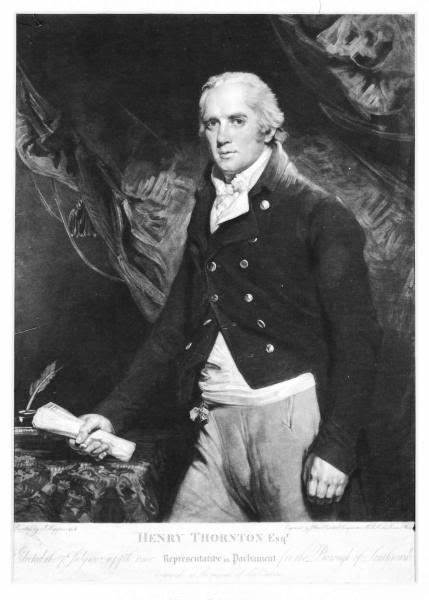

Reformer Henry Thornton dies at William Wilberforce’s house in London, England. A banker and Parliamentarian, he had been the financial brains behind the social schemes of the philanthropic and anti-slavery group known as the Clapham Sect.

1852

Elizabeth Prentiss was a frail woman who suffered intensely from chronic insomnia all her life. Few knew it. Despite her misery, and a “morbidly-sensitive, melancholy temperament,” the face the world saw was usually a radiant one for she strove hard to overcome the irritableness her illness engendered. She was described as a bright-eyed woman with a keen sense of humor.

For several months in her early twenties, she was in agony because of her conviction of her sinfulness and lack of concern for the things of Christ. She considered herself a hypocrite, although all of the evidence indicates otherwise. At that time she was a teacher, deeply concerned for the salvation of her pupils, many of whom she led to Christ. When this crisis was over, she moved into a deeper joy than she had previously experienced. Not long after this she wrote, “Sometimes my heart feels ready to break for the longing it has for a nearer approach to the Lord Jesus than I can obtain without the use of words, and there is not a corner of the house which I can have to myself.”

The daughter of one beloved pastor (Edward Payson), Elizabeth married another (George L. Prentiss) in 1845. As a housewife and mother, her activities included the writing of religious books, novels and poems. Although many of these are still available, we remember her most for a single notable hymn:

More love to thee, O Christ,

More Love to Thee!

Hear thou the prayer I make

On bended knee;

This is my earnest plea,

More love, O Christ, to thee,

More love to thee!Once earthly joy I craved

Sought peace and rest

Now thee alone I seek

Give what is best;

This all my prayer shall be,

More love O Christ, to thee,

More love to thee…

This was written in 1856 at a time of serious illness. Thirteen years would pass before she showed the lines to her husband. Composer George W. Doane later set them to music.

One of the darkest days of her life was on January 16, 1852 when her son Eddy died. The five-year-old had broken into a rash and fever. Elizabeth did the little that the doctors could suggest in an attempt to save his life. After Eddy died she recognized that going to Jesus was a great blessing for him, however much pain it cost her; and she wrote lines in which she urged him, “O, hasten hence! to His [Christ’s] embraces, hasten!” Dedicated to Christ, Elizabeth sought to live a life of joy. She said, “Much of my experience of life has cost me a great price and I wish to use it for strengthening and comforting other souls.”

1860

As a young man, Hudson Taylor determined to become a missionary in China, where he eventually landed in 1854. The needs he saw around him were so great that he felt overwhelmed.

He founded the China Inland Mission and saw over one hundred workers enlist in it. But in a letter that he wrote to relatives in England on January 16, 1860, he would have rejoiced for far fewer workers.

“Do you know any earnest, devoted young men desirous of serving God in China, who not wishing for more than their actual support would be willing to come out and labour here? Oh for four or five such helpers! They would probably begin to preach in Chinese in six months’ time; and in answer to prayer the necessary means would be found for their support.”