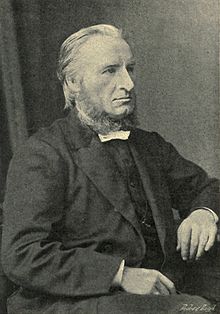

1921

On this day, January 6, 1921, Alexander Whyte died quietly in his sleep. The eighty-five-year-old Scotsman had risen from poverty and illegitimacy to become one of the most prominent pastors in Scotland. His faith began when he was young. Sunday mornings, his hardworking mother, Janet Thomson, took him to the Free Church. In the afternoon, he attended the Relief Church with his grandmother. He capped off Sunday by attending the Auld Licht (Old Light) Church by himself in the evening. He dreamed of becoming a minister.

Although his mother could not afford to pay for his education (those were the days before governments educated everyone), Alexander was determined to learn. He subscribed to a magazine on self-education and paid a younger boy to hold up borrowed books for him so that he could read while be made shoes as an apprentice.

With this learning under his belt, he became a teacher. To keep ahead of the more advanced pupils, he studied late at night after class was done. The following year, a sympathetic minister taught him Latin and Greek so that he could go to university–if the funds could miraculously be found.

Alexander swallowed his pride and wrote to the man who had fathered him and then abandoned his mother. John Whyte had become a successful businessman in New York. He sent Alexander the money. Teaching factory workers to cover his living expenses, Alexander threw himself into his studies. He graduated second in his class. Because of his own experiences, he never forgot the poor.

Eventually, Alexander headed the largest Scottish church and was a college president. A powerful speaker, in his very first sermon he emphasized the need to focus one’s attention on Christ. Throughout his life, he always stressed the importance of a personal religious experience. Christianity was not just a matter of keeping commandments. Many of his sermons, with vivid illustrations, found their way into print.

A sermon he preached on prayer is a good sample of his style: “We hate God, indeed, much more than we love ourselves. For we knowingly endanger our immortal souls; every day and every night we risk death and hell itself rather than come close to God and abide in secret prayer. This is the spiritual suicide that we could not have believed possible had we not discovered it in our own atheistical hearts. The thing is far too fearful to put into words. But put into words for once, this is what our everyday actions say concerning us in this supreme matter of prayer. ‘No; not tonight,’ we say, ‘I do not need to pray tonight. I am really very well tonight. And besides I have business on my hands that will take up all my time tonight. I have quite a pile of unanswered letters on my table tonight. And before I sleep I have the novel of the season to finish, for I must send it back tomorrow morning…”