1605

Have you ever heard anyone say, “He’s just an ordinary guy?” Curiously, the word guy has its roots in a l7th century plot to blow up the British Parliament.

Religion and politics were inseparable in early England. When Pope Pius V excommunicated Queen Elizabeth in l570, English Catholics did not like obeying a queen that their pope had banned from their Church. Some even plotted to assassinate her. During Elizabeth’s reign, her “secret service” uncovered three Catholic plots to remove her from the throne.

After her death in 1603, small groups of Catholics believed the disease of Protestantism in England called for a violent remedy. They made plans to blow up the English House of Lords on the day Parliament was to meet. Many of the country’s leaders would be killed–King James I, his royal family, the House of Lords, and many from the House of Commons. With all these leaders dead, the plotters hoped to see England returned to Catholicism. It would be like the discovery of a plot in America to blow up Congress at the time the President was giving his annual “State of the Union” address with all the key government officials in attendance.

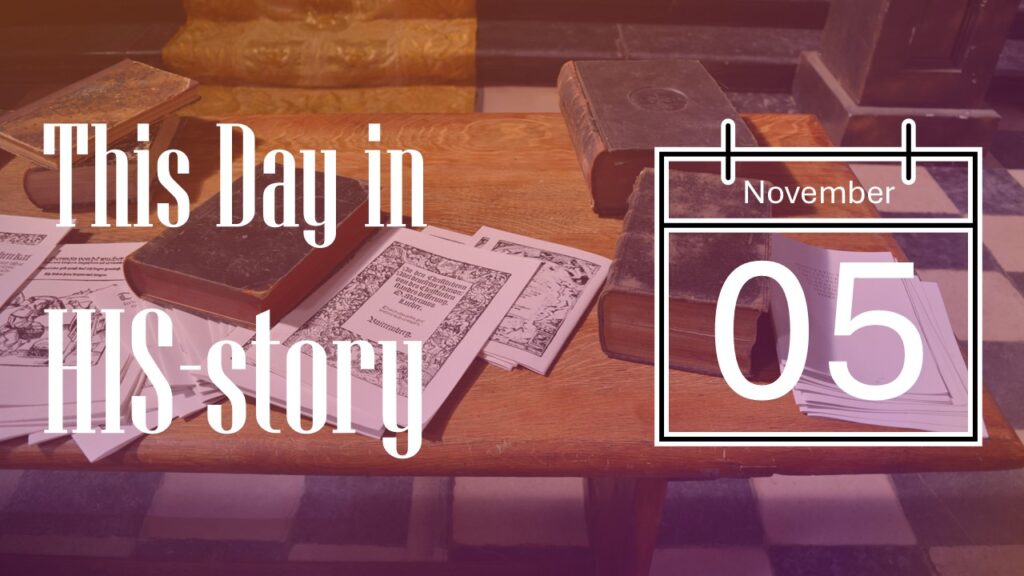

Working for more than a year, the conspirators in the British plot rented a vault under the House of Lords. They planted 36 barrels of gunpowder which they hid under some firewood, and then waited to light the match when Parliament opened. But wishing to spare certain Parliamentary friends, the conspirators dropped warnings. Learning of the plot, the king’s men captured Guy Fawkes skulking near the gunpowder either near midnight on November 4 or in the early hours of this morning, November 5, 1605.

Tortured in the Tower of London, Fawkes soon revealed the whole plot and named his accomplices. Many others also revealed information. After lighting the fuse, he was to escape in a boat over the Thames. There was to have been a rising of Catholics in the Midlands and kidnapping of the King’s children. Meanwhile, most of the main band of conspirators were killed in a shoot out. Afterwards, as is usual in such cases, Parliament passed even stricter laws against Catholics.

Popular consensus held that the discovery of Guy Fawkes and his plot was God’s Providence protecting England. The British still ceremoniously search the cellars before opening each session of parliament, and on Guy Fawkes Day, a national holiday, a dummy of Guy Fawkes is hanged in effigy. Thus, the English word “guy”, has come to mean a stuffed dummy. In America the word simply refers to an ordinary fellow.

1677

Solomon Stoddard had a dilemma on his hands. New England Puritans held to a Covenant Theology. In its simplest terms this said that any group of people who pledged to each other to obey God’s word for the good of all could form a congregation or church. Covenant members had to give a verbal testimony of their experience of grace. Stoddard’s dilemma grew out of Covenant Theology.

Covenant members married and had children and grandchildren. What should be done with these newcomers? Had they experienced grace? Were they part of the church or not?

Richard Mather drafted a solution in 1662. It was called the Halfway Covenant. Under it, infants could be baptized, but the children of covenant members were not allowed to partake of the Lord’s Supper until they made a confession of personal faith at the age of fourteen or so. Unless churchgoers made such a confession of faith, they should not partake of the bread and wine.

Solomon Stoddard, the Congregational minister at Northampton, Massachusetts, pointed out the dilemma in Mather’s Halfway Covenant. Under it, no one was allowed to partake of the Lord’s Supper until he had certain knowledge and assurance of salvation; without this knowledge, attendance at the sacrament was damning. However, under that same theology, no man could be absolutely sure he was eternally saved. The very thing you couldn’t be sure of was the one thing the Halfway covenant required you to declare. But if no one could be absolutely sure he or she was eternally saved, how could anyone make a declaration of salvation in order to take the elements?

Stoddard’s solution was to allow any well-behaved churchgoer who chose to do so to partake of the bread and wine even if he or she wasn’t sure of salvation. Stoddard argued that if they were not saved, taking the bread and wine might help them secure saving grace or even convert them. On this day, November 5, 1677, he adopted this new practice.

Since Stoddard had a good deal of influence, his example was followed by most preachers in Western Massachusetts. Ironically, one who did not follow him was his own grandson, Jonathan Edwards. This brilliant thinker, who succeeded his grandfather as pastor of Northampton, was not persuaded that open communion should be allowed. He charged that the Puritans had drifted into a religion of works. Seeking to restore a purer Calvinism, he rejected Stoddard’s principle. In 1750, his congregation booted him out of the pulpit.

1858

“You will be eaten by cannibals!” Mr. Dickson thought John Paton was foolish to go as a missionary to the New Hebrides. Not twenty years earlier, John Williams and James Harris had become the main course of a cannibal meal.

John Paton could not to be turned from his purpose. “Mr. Dickson, you are advanced in years now, and your own prospect is soon to be laid in the grave, there to be eaten by worms; I confess to you, that if I can but live and die serving and honoring the Lord Jesus, it will make no difference to me whether I am eaten by cannibals or by worms; and in the Great Day my resurrection body will rise as fair as yours in the likeness of our risen Redeemer.”

John did not step straight from school into foreign missions. As a young man, he become an evangelistic worker in Glasgow, visiting home after home with the gospel, in spite of threats, abuse and the contents of chamber pots dumped on him. Under those conditions, he learned the steadiness and determination that carried him through his later adventures. The people of Glasgow came to love him so much that they begged him not to leave.

With his wife, Mary, John sailed from Scotland in December, 1857. On this day, November 5, 1858 they landed on the island of Tanna in the New Hebrides, an island chain northeast of Australia. With them was another young missionary, Joseph Copeland.

The people were as fierce as he had been told. Cannibal celebrations took place in sight of the Patons’ home and human blood fouled the drinking water. The natives frightened Joseph Copeland so much that he lost his wits and died; they continually threatened John. Time and again they lifted their guns to shoot him, or raised their axes to bash him in the head, but always they held back as if restrained by a greater power. Early the next year, Mary bore a son. Both mother and child came down with fevers and died. With a breaking heart, John dug their grave and laid them in it. Later he said, “But for Jesus, and the fellowship He vouchsafed me there, I must have gone mad and died beside that lonely grave!”

John remained on Tanna. He went from village to village telling of the love of Christ and translating Scripture into the Tannese language. But finally, when all his supplies were stolen and starvation stared him in the face, he made his way across the island to the settlement of a second missionary. Exhausted he fell asleep. The Tannese surrounded the home and set an adjacent building on fire. It appeared the missionaries would burn to death. But a tornado whipped across the compound, dousing the fire. The savages fled in terror. The next day, a sail appeared and the missionaries escaped on the boat.

After leaving Tanna, John remarried and worked on a smaller island. He had the joy of seeing the people of Aneityum come to Christ in a way the people of Tanna never had.

1960

Death of Donald Grey Barnhouse, American Presbyterian clergyman. In 1927 he began a thirty-three-year pastorate and radio ministry at the Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia; during his last ten years, Barnhouse edited Eternity magazine, which he had founded. He authored over thirty books on the Scriptures and on the Christian life.