1833

No man fought harder to abolish slavery than William Wilberforce. A member of Parliament, he introduced antislavery measures year after year for 40 years until he retired in 1825. On this day July 26, 1833, as he lay dying, word was brought him that the bill to outlaw slavery everywhere in the British empire had passed in Parliament. The dream for which he had struggled for decades was now within sight of fulfillment!

Wilberforce had not always been a serious opponent of slavery. As a youth he was a witty, somewhat dissipated man about town who had misspent his time at Cambridge. He was invited to every party.

A friend of William Pitt (who became Prime Minister) and a member of Parliament, Wilberforce seemed assured of a bright political future. And then in 1784, after winning his election in Yorkshire, he accompanied his sister to the Riviera for her health. Isaac Milner, a tutor at Queen’s College Cambridge and acquaintance from college days was asked along. Isaac agreed.

Milner had become a deep and evangelical Christian. He began to persuade Wilberforce to commit his life to Christ. Wilberforce had always thought himself a Christian. Now he saw that total commitment to Christ was needed. He struggled in anguish for several months. During that time he read Philip Doddridge’s The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. Here was a faith far deeper than anything he had known. Gradually he yielded.

At once he began to wonder if it was proper for him to hold a seat in government. He confided in Pitt. Pitt, wanting Wilberforce as an ally, urged him to remain. Unsettled in his conscience, Wilberforce spoke to the rector John Newton. Newton, best remembered as the author of the hymn “Amazing Grace,” had been converted while a blasphemous sailor and slaver. He counseled Wilberforce to remain in politics and champion good causes.

Friends suggested that the young man take up the slavery issue. Pitt also requested it. After many doubts, Wilberforce decided it was what God wanted. He also felt he must tackle causes which would raise the standard of life and morals in England. The friends who gathered around him became known as the Clapham sect because most lived in the village of Clapham.

Rarely in history have so many owed so much to so few. These dozen or so Clapham men and women not only fought against slavery but also against every sort of vice. Many were wealthy. They employed their worldly goods in behalf of godly causes. Education of the masses, support of Bible societies, private charity, protection of chimney sweeps, creation of Sunday Schools and orphanages–these and dozens of other causes received their attention. But it is the abolition of slavery which remains their greatest achievement.

1890

HT: Christian History Institute

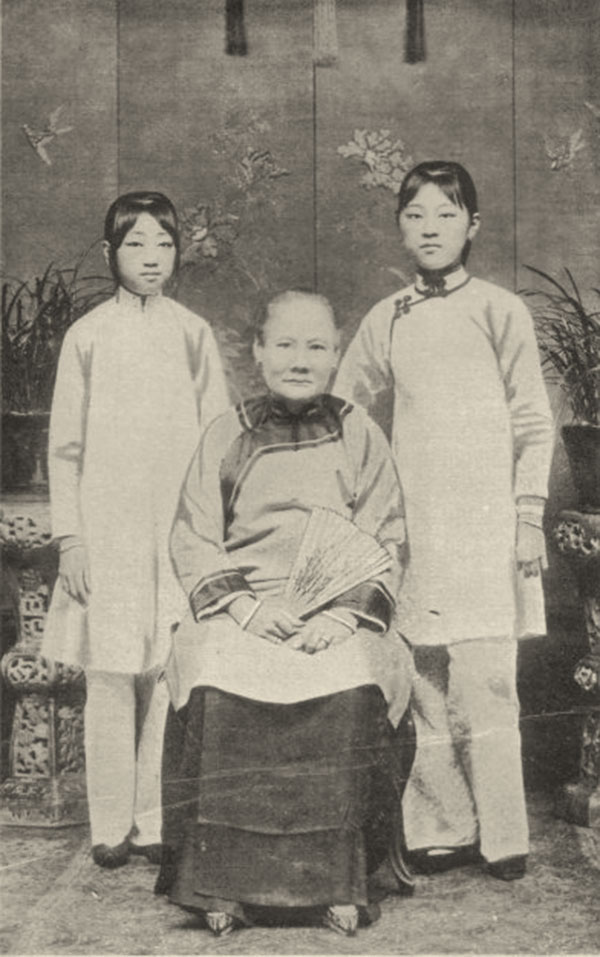

Mrs. Ahok was an upper class Chinese woman—her bound feet were only two and a half inches long. Through studying the Bible to learn English, she was converted from open idolatry to ardent Christianity. Her status allowed her into the homes of other elite Chinese women whom she sought to lead to Christ.

Mrs. Ahok with granddaughters

A missionary friend, Miss Bradshaw, invited her to England and she agreed to go, believing she was led by the Holy Spirit. She spoke to large groups, giving her testimony and pleading that more mission workers come to China. Non-Christians interested in China came to these meetings, and some became followers of Christ. Learning that her husband was ill, Mrs. Ahok left England to return to China by way of Canada. Her husband died before she got home. Chinese friends criticized her, saying the tragedy happened because she abandoned her Chinese gods. However, three new mission societies were formed as a result of her short visit to Canada. At Vancouver she had to wait some days for her steamer, and wrote to Miss Bradshaw on this day 26 July, 1890.

“All well, all peace. From the time I left England a month has passed away. I keep thinking constantly of the meetings in England which we had together. Now we are in this place waiting for the ship and therefore we had this very good opportunity for work. I have been invited by the minister of the church here to speak at meetings. I have done so six times. Because this is a new place, and there are men and women who do not at all believe the Gospel, but who like to hear about Chinese ways and customs, therefore they all greatly wish me to go to these meetings. I think this is also God’s leading for us, that we could not proceed on our journey, but must spend this time here….”

Burton, Margaret E. Notable Women Of Modern China. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1912.

Source