Here’s this week’s inspirational delve into the past by Paul James-Griffiths of Christian Heritage Edinburgh. Paul writes, “Having put in the foundation for Scotland’s vision for world mission during the last few weeks, we are now in a position to write a series about key individual enablers and missionaries. For the next few weeks we will focus on India. This week we will look at a largely forgotten Scottish Christian called Charles Grant, who prepared the way for William Carey and others to be allowed to take the gospel to India.”

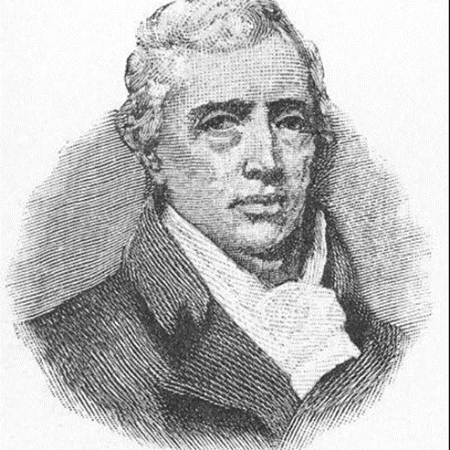

World Mission Series (1): India and Charles Grant (1746-1823)

India: a nation of vibrant colour, beauty, and complex paradoxes; a nation drenched with Hinduism’s millions of gods; a vortex that sucks up all religions and philosophies, and transforms them into a multi-coloured tapestry of oneness; a nation whose gurus seek to kill the mind and liberate themselves from maya, the illusion of our earthly existence, to be absorbed into a universal unknowing consciousness. Side by side alongside Hinduism, itself a merging of many Indian pagan beliefs, would arise Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, and other religions.

Image: Charles Grant (1746-1823), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Our Scottish Christian connection begins with Charles Grant (1746-1823) from Aldourie, near Inverness. Like so many from Scotland’s Reformation heritage, he grew up in poverty, but would go on to accomplish extraordinary achievements. Arriving as a young man in Bengal in 1768 he found himself sandwiched between two British worldviews: the colonial, materialistic, exploiting, and self-centred identity, and the Christian identity that sought to love and emancipate India. He witnessed his Christian boss, Richard Bechner, pouring himself out to feed up to seven thousand Indians a day during the raging of a ferocious famine. With the death of his two daughters from smallpox, Grant was flung into a quest for God and eternal life, leading to his Christian conversion in 1776.

On 17th September 1787, Grant sent his appeal for missions to India to fourteen well-known public figures in Britain. Of these only one replied: Revd Charles Simeon of Cambridge, who caught Grant’s passion for India, and stirred up his Christian students. Of these early missionaries Henry Martyn (1781-1812) went on to translate the New Testament into Urdu and Persian, and to develop Hindi, which is spoken today by almost half of India’s people. Claudius Buchanan (1766-1815) from Cambuslang near Glasgow, served as the vice-principal of India’s first British college at Fort William in 1800, where he oversaw the development of India’s languages through Bible translation, and worked together with William Carey.

Grant himself would become a good friend of William Wilberforce, and wrote a document calling for mission to India and Asia in 1792 (the same year in which William Carey published An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens). Although Grant’s document was not officially published until 1797, it had already become the chief evidence used in Britain’s Parliamentary debate about mission to India in 1793, preparing the way for missionaries, such as William Carey, to be established in India under British rule, and for Parliament’s acceptance of missionaries in 1813.

Grant’s vision for India contained within it the gospel, national education, agriculture, science, and technology, all of which would be taught in English. It was hoped that through this model, India would be drawn away from its superstitions like widow burning (sati), sacrificing the firstborn child in the River Ganges, and other practices. He was an M.P. for Invernesshire from 1802-1818, but he also strove to model education in India when he was the Chairman for the East India Company from 1805. From this position of influence Grant could sponsor many missionaries in India, such as Henry Martyn and Claudius Buchanan, and prepare the way for mission there.

“Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations” (Matthew 28:19, NKJV).