339

Suppose you are a survivor of an outlawed organization whose origins go back to around 1700, seventy-six years before America became an independent nation. “Tell the story of your people,” you are urged.

The problem is, your people were an illegal group. In fact, the government tried to exterminate them! Their leaders were captured and killed and many letters and books burned. They left no public festivals, no monuments–very little by which historians ordinarily trace history. And to make your task more challenging, your people were scattered over most of the known world. How could you possibly put together their story? That is the kind of task Eusebius tackled.

His people were the Christians who had been persecuted for almost three hundred years. A measure of peace came to the believers when Constantine became emperor. At last the story of the church could be told.

Eusebius was the one for the job. He had already prepared a chronology of the Bible and early church, trying to establish the dates of Christ’s death and the events that followed. This was a difficult undertaking because many different calendars were in use at the time and he had to match up events recorded under one system to events recorded under others.

Eusebius’ ten-volume history is our best authority for early Christian history. We owe him a special debt because he quotes from many sources that no longer exist. We are blessed that he showed interest in a broad range of material. He traced the lines of apostolic succession in key cities. Thus we know how the church progressed in the big towns. The church has always been nourished with the blood of martyrs. Eusebius told the stories of many who suffered for Christ.

He was also interested in debates over which books should be in the Bible and he gave us various views of the matter. Because of this we know a good deal about how we got the New Testament. Eusebius also traced the threads of heresy. Through him we know of challenges to orthodoxy in the early centuries of the faith. Above all, Eusebius described how God preserved the church and poured his grace upon it. Eusebius even followed the woeful fate of the Jews and their struggles.

Eusebius died on this day, May 30, 339. He was seventy-four years old. In addition to all his other writings, he left behind him commentaries on Isaiah and on the Psalms, a geography of the Bible, and a concordance of the Gospels. He wrote books to clear up differences in the Gospels. Finally he produced an account of the Martyrs of Palestine whom he had personally known. But his history remains his most important contribution to the church, and the one by which his name will always be remembered, for it gave us our past.

1865

ON THIS DAY, 30 MAY 1865, Wesleyan Methodist missionary Dr. James Egan Moulton arrived in the Pacific nation of Tonga, an archipelago of over 150 small islands. Tonga’s Christian ruler, King George Tubou, had requested the brilliant young educator-evangelist by name. Like the prophet Hosea, King George lamented that his nominally Christian people were being “destroyed for lack of knowledge.” Although blessed by the work of previous missionaries, they remained largely ignorant of biblical truth. But their hearts and minds were open and the time was ripe for learning.

Just a few years earlier, Moulton would never have dreamed of becoming a missionary, having been dogged by a noticeable stammer from his youth. Nevertheless, he had tenaciously persisted in public speaking, eventually earning the respect of his mocking classmates. As a young man he unexpectedly wowed a foreign missions meeting; in an uncanny foreshadowing, the topic of his speech was Tonga’s pious sovereign, King George! Because of this incident, Moulton was advised to leave his studies as an apprentice chemist to become a missionary. Yet his stammer stood squarely in the way of this change of course.

“Oh Lord,” he prayed, “I am perfectly willing to work for Thee, but oh! remove this impediment!” Immediately, the stammer left completely and permanently. This miracle strengthened more than just his voice: it inspired him with lifelong zeal and total reliance upon God’s provision.

Though a promising candidate for the ministry, Moulton was unreasonably rejected. While he waited for his way to become clear, he took a clerical job at a shipping company where his talents gave him excellent prospects. Untempted by worldly success, however, he reapplied for the Methodist ministry, and this time his offer to serve in foreign missions was accepted.

Initially delegated for China, Moulton was reassigned to Fiji, a much larger Pacific island nation than Tonga. With amazing quickness he gained fluency in Fijian, even writing an entire sermon in the language during the long ocean voyage. Once in Australia, however, Methodist leaders seized upon the highly-qualified Moulton to be the inaugural headmaster for Newington College, a brand-new seminary attached to a primary and secondary school. His enthusiasm, approachability, and musical abilities made him popular there. While setting a high standard in the classroom, he was also an active participant in the students’ recreation.

Moulton’s engagement to a young lady back in England survived their separation of over a year, and Emma Knight traveled to Australia to join him. Married two days before Christmas in 1864, they eagerly awaited orders from the mission to proceed to Fiji, though Moulton was sorry to leave Newington. However, King George’s request, likely inspired by news of Moulton’s success as an educator, changed his plans again.

On this day in 1865, after their ship barely survived a stormy voyage, Moulton and his bride found themselves in Tonga. Moulton threw himself into learning Tongan, and just five days later he was reading the Bible and the hymnal in Tongan for Sunday services. In only three months he was preaching in the language!

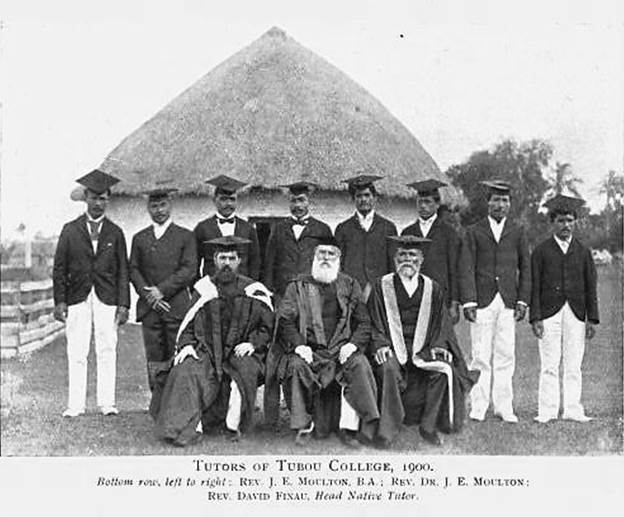

Moulton immediately took on the daunting task of developing Tongan higher education from scratch, founding Tubou College (named after the king), an institution that would go well beyond the elementary level of existing schools and prepare students for both ministerial and governmental positions. With the king’s support, he was able to enforce uniform school discipline despite Tonga’s ingrained double standard between upper and lower social classes.

Moulton obtained a printing press and taught himself to operate it so he could publish Tongan-language textbooks he authored in his “spare time.” The musical program suffered a temporary setback when Moulton’s students refused to learn their Do-Re-Mi’s; Moulton found to his chagrin that the solfege syllables spelled out Tongan swear words, and he had to create a new system! He soon added music books to his printing operation.

With Tonga’s new college an astounding success, Moulton returned to England temporarily to work intensively on translation. After his return to Tonga, his relations with King George soured because the king believed rumors that Moulton was working to annex Tonga for Britain. Despite serious political and denominational conflicts, the tragic loss of his daughter, and a near escape from drowning, Moulton worked tirelessly. However, the ongoing conflict with the king forced him to leave Tonga for Australia in 1888. Happily, the situation improved by 1891, and the breach with King George was healed before the ruler died.

In 1893 Moulton became president of both Newington College (which he saved from financial ruin) and the New South Wales Methodist Conference. Meanwhile, he remained closely involved with Tubou College and continued to write beloved Tongan hymns. His total mastery of Tongan idiom enabled him to prepare a dynamic revision of an earlier Bible translation. Moulton’s version, which he worked on for years between his many other projects, was published in 1906 and remains in use today.

Though afflicted by asthma, Moulton continued translating in retirement until he went to his reward on May 9, 1909. Wrapped in a finely woven Tongan mat fit for a high chief, he was buried in Sydney with a copy each of the Tongan Bible and hymnal. The Tongans flew their capitol building flag at half-mast for three days.

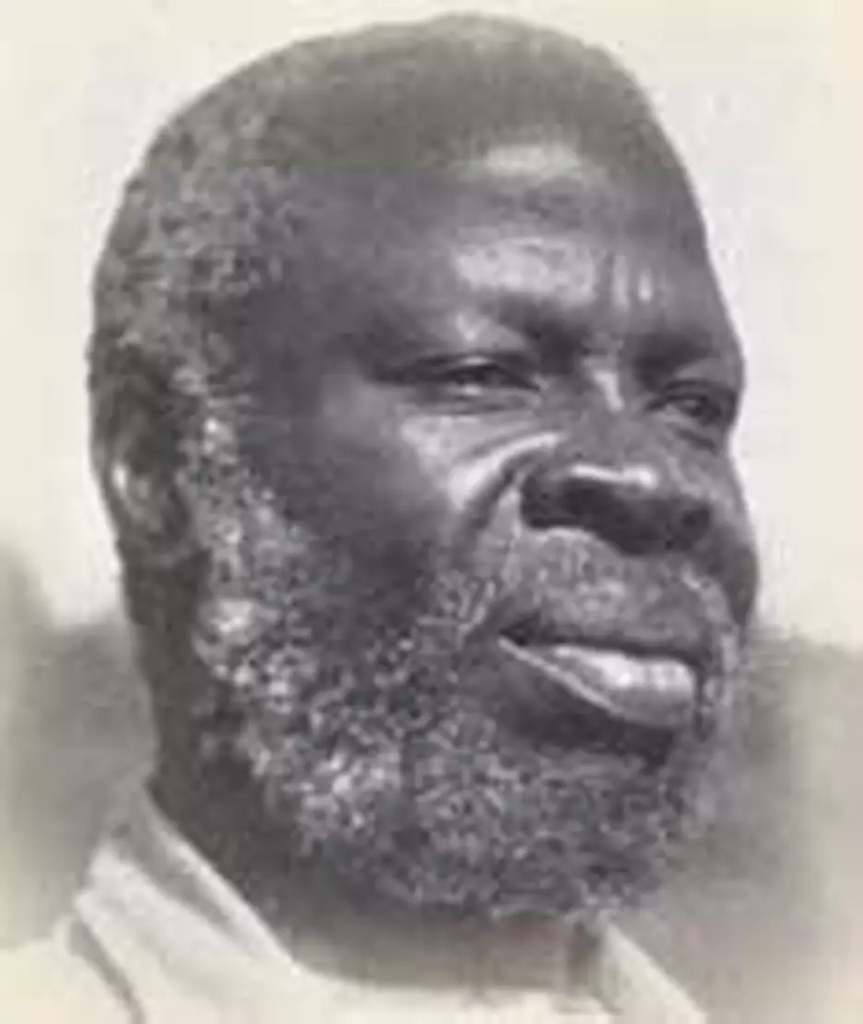

Apolo (also known as Kivebulaya) should have been discouraged. The Uganda-born man had accepted a request to go to Mboga in the Congo to teach about Christ. He went, carrying a hoe over his shoulder, because two earlier Ugandan missionaries had been forced out when the people of Mboga refused to sell them food. The people did not appreciate the Church’s prohibition on sorcery, polygamy and drunkenness, and made it tough for the evangelists.

The same situation arose with Apolo and he was glad he had brought his hoe. The people of Mboga tried to starve him out, but he raised his own food. Where starvation did not succeed, a false accusation almost did. The chief’s sister impaled herself on a spear that had been left in some tall grass. Everyone blamed Apolo, who, of course, did not even own a spear. After beating him severely, they left him to die. A faithful Christian woman nursed him back to life.

During one particularly bad hour, he had a dream. As he told it later, “I saw Jesus shining like the sun. He said to me, ‘Take heart, for I am with you.’ Since that year whenever I preach, people leave their old customs and repent.” Whatever discouragement Apolo felt left then.

Perhaps Apolo remembered how hard-hearted he himself had been in his years as a young dope-smoking soldier. And yet the gospel had penetrated his heart and changed him. He was deeply impressed with the life and teaching of missionary Alexander Mackay. The rough young man dropped his birth name Waswa Munubi and taken the baptismal name Apolo (after Apollos, the evangelist mentioned in the book of Acta). He returned to Mboga and began to preach again.

Apolo died in Mboga on this day May 30th, 1933. At his earlier request, he was buried with his head to the west, because he saw that the gospel needed to be carried across the Congo in that direction.

He had planted well and the church flourished after his death. Thirty years later, it had 25,000 members. Today, there are over half a million. Without the faithfulness of this one man, the Church of England would not exist in such numbers in the Eastern Congo today.