1910

HT: Christian Classics Ethereal Library

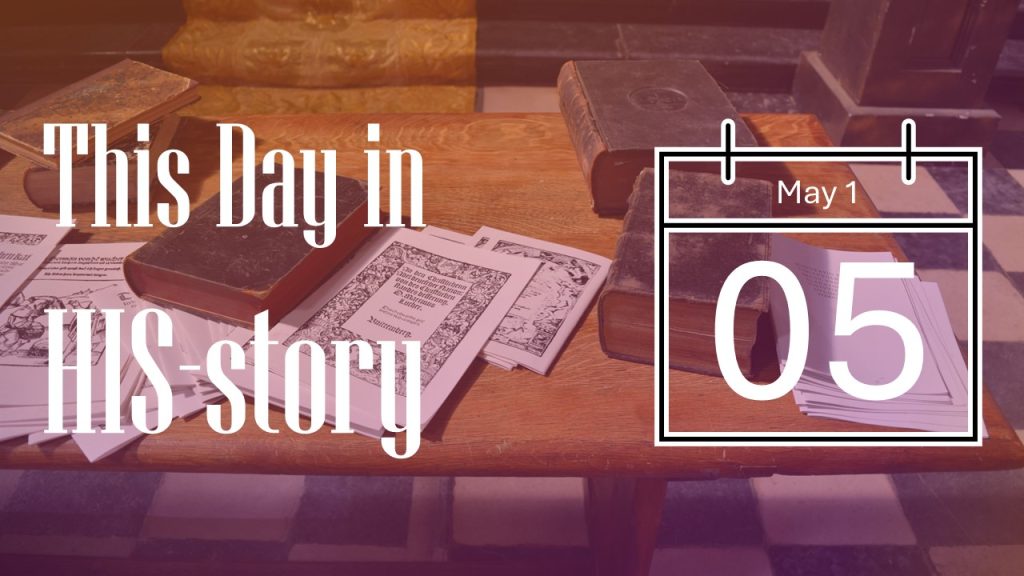

Alexander Maclaren was born in Glasgow on February 11, 1826, and died in Manchester on May 5, 1910. He had been for almost sixty-five years a minister, entirely devoted to his calling. He lived more than almost any of the great preachers of his time between his study, his pulpit, his pen.

He subdued action to thought, thought to utterance and utterance to the Gospel. His life was his ministry; his ministry was his life. In 1842 he was enrolled as a candidate for the Baptist ministry at Stepney College, London. He was tall, shy, silent and looked no older than his sixteen years. But his vocation, as he himself (a consistent Calvinist) might have said, was divinely decreed. “I cannot ever recall any hesitation as to being a minister,” he said. “It just had to be.”

In the College he was thoroughly grounded in Greek and Hebrew. He was taught to study the Bible in the original and so the foundation was laid for his distinctive work as an expositor and for the biblical content of his preaching. Before Maclaren had finished his course of study he was invited to Portland Chapel in Southampton for three months; those three months became twelve years. He began his ministry there on June 28, 1846. His name and fame grew.

His ministry fell into a quiet routine for which he was always grateful: two sermons on Sunday, a Monday prayer meeting and a Thursday service and lecture. His parishioners thought his sermons to them were the best he ever preached. In April 1858 he was called to be minister at Union Chapel in Manchester. No ministry could have been happier. The church prospered and a new building had to be erected to seat 1,500; every sitting was taken. His renown as preacher spread throughout the English-speaking world. His pulpit became his throne. He was twice elected President of the Baptist Union. He resigned as pastor in 1905 after a ministry of forty-five years.

Maclaren’s religious life was hid with Christ in God. He walked with God day by day. He loved Jesus Christ with a reverent, holy love and lived to make Him known. In his farewell sermon at Union he said: “To efface oneself is one of a preacher’s first duties.”

1936

HT: Dan Graves and Raymond Davis in Fire on the Mountains

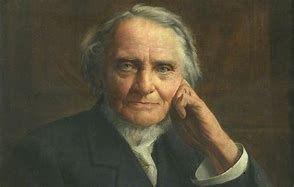

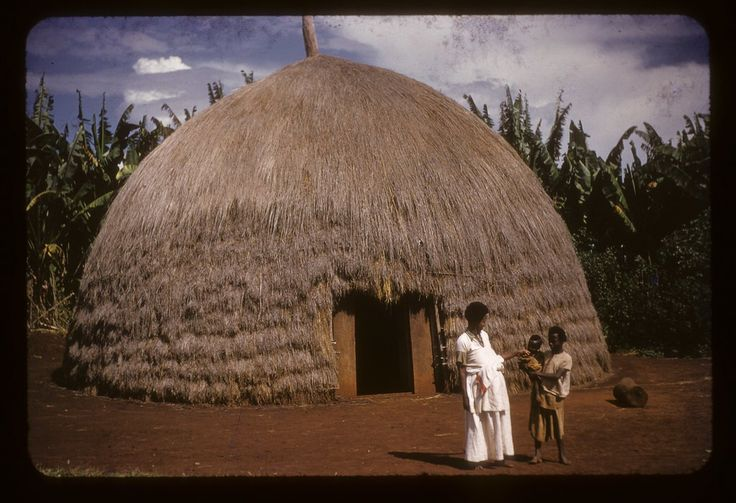

In 1937, after 9 years of work in Ethiopia by Western Missionaries from the Sudan Interior Mission there were only 48 known indigenous believers made up of Wallamo tribes people (who had previously been devil-worshippers).

A year earlier, on this day, May 5, 1936, Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, had fallen to Mussolini’s invading armies. Emperor Haile Selassie fled. Barefoot Ethiopian soldiers resisted bravely against tanks and mustard gas, but the Italians won. Soon the victors came for the missionaries, who left just 48 baptized Christians behind them in Wallamo. They were all new in the faith and no longer had any missionaries to guide, teach, or instruct them. These had the Gospel of Mark and a few other passages of scripture in their language, but few knew enough to read even that. Several of the Christians already knew, first hand, what persecution was like, having experienced it from heathen neighbors.

The missionaries prayed constantly. “We knew God was faithful,” one missionary wrote. “But still we wondered—if we ever come back, what will we find?” The believers faced severe persecution from the Italian troops but stayed true. Beaten, tortured, killed, they stood fast, heroes of God. They even sang when told to tear their

church down–and cheerfully obeyed. Other Christians died of cold at night in unheated jail cells. One of their leaders, Toro, was thrown face down in the mud of a jail cell and beaten with a hippo-hide whip. “Where is the God who can deliver you out of our hands?” he was asked. “My God is able to deliver me–if he chooses–and if not, He has promised to take me to heaven to be with Him there.” Soon afterward, a terrible storm blew off the prison roof and melted its mud bricks. The guards were terrified. They pleaded with Toro to pray for

them, and then released him!

Raymond Davis tells of the love demonstrated by believers for each other during this period of affliction, which in turn made a major impression on unbelievers. For example, no provision was made to feed the prisoners in

jail by the invading army. This was the responsibility of relatives and friends. Christians in the prisons had no problem, though. They were well cared for by friends and family. In fact, so much food was brought them by fellow believers and church groups that enough remained to feed the unbelieving prisoners also. This observable love, vibrant though nonverbal, brought many to seek the Lord. Such love was previously unheard of. As a result the word spread far and wide. Nonbelievers sought out believers to learn more about the Christian faith. When prisoners who had come to know Christ while in jail were released, they went back

home and attended the nearest church.

These Protestants perceived the persecution as motivated not by politics, but by differences in religious faith, since Catholic priests promised them freedom if only they would kiss the crucifixes held up to them. To the Wallamo, this seemed like a return to the idolatry they had recently left, and they refused freedom at that price. Their faith and courage attracted others to Christ.

On this day, May 5, 1941, five years to the day that he had left Ethiopia, Haile Selassie returned. The missionaries returned to the capital, too. What would they find? Reports reached them from Wallamo. Not only had the church survived, it had grown. Not only had it grown, it had grown more than 200 times greater. The 48 believers had become 10,000!

The missionaries credited the Holy Spirit who guided the suffering Christians. Cheerful and forgiving under enemy savagery, they proved that their faith was genuine. They sang songs with encouraging words: “If we have little trouble here, we will have little reward there. We will reign.”

By 1950 the numbers had increased to 240,000; and by 1990 to 3,500,000